Parkeology 005: Don’t Buy Sugar

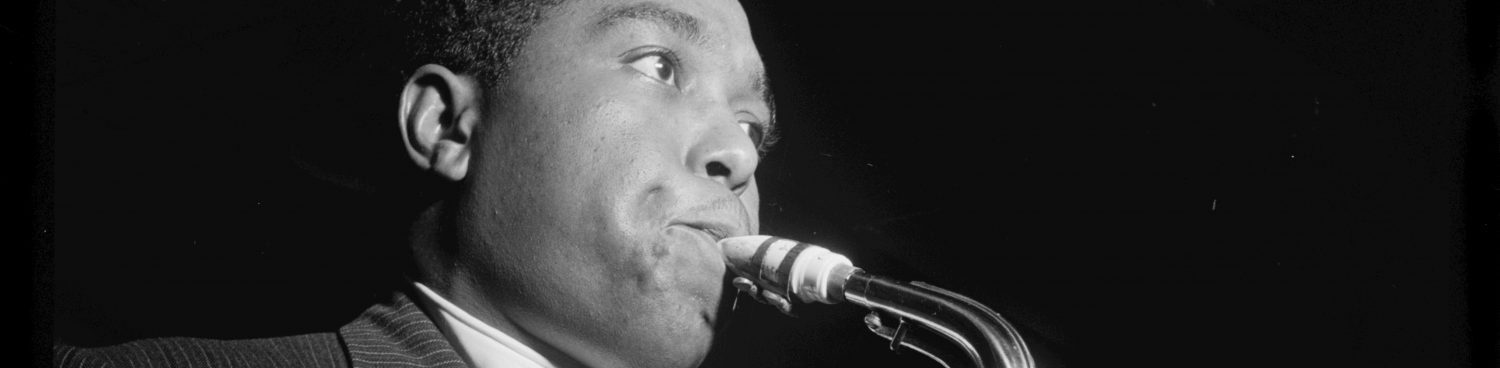

I learned to play the first eight bars of “Lazy River” and I knew the complete tune to “Honeysuckle Rose.” So I took my horn out to this joint, where a bunch of fellows I had seen around were, and the first thing they started playing was “Body And Soul,” long beat. So I go to playing my “Honeysuckle Rose” and they laughed me off the bandstand.” – Charlie Parker

That, in so many words, is Bird’s epic tale of humiliation at the hands of Jimmy Kieth and associates, related in the Stearns interview, May 1950. Bird displays his photographic memory by naming all the musicians on the bandstand that day, including Shibley Gavan, although, to be fair, who could forget a name like that?

Jazz writers have long focused on the psychological aspects of this humiliation, but the musical implications, as far as I can tell, remain unexplored. What attracted nascent Bird to these two tunes, and what theoretic principles might he have extrapolated from them?

It’s probably best to put the forest before the trees. There’s plenty of evidence that Honeysuckle Rose was meaningful to Bird, in more ways than one. It was the first tune he ever recorded, together with Body And Soul, in a seeming riposte to Jimmy Keith. The sound quality of this solo saxophone recording, known as Honey and Body, would render it unlistenable if not for its historical importance. Just a few months later, in November 1940, Bird recorded Honeysuckle Rose a second time, with Jay McShann, along with Body And Soul. (A pattern begins to emerge.)

Statistically, Bird’s favorite set of changes is I Got Rhythm, but Honeysuckle Rose forms the basis for Scrapple From The Apple (Dial 11/4/47) which became a cornerstone of his live repertoire from 1948 onward. It also forms the basis for Marmaduke (Savoy 9/24/48), a tune whose charm conceals its significance.

Bird was drawn to melodies with prominent 9ths: Out Of Nowhere, Body And Soul, Star Eyes, East Of The Sun, If I Should Lose You, Laura, My Little Suede Shoes, and more. Among his own compositions, Red Cross, Cool Blues, Now’s The Time, Barbados, Bird Feathers, and An Oscar For Treadwell come to mind. And then there’s the Joe Louis of examples, Cherokee.

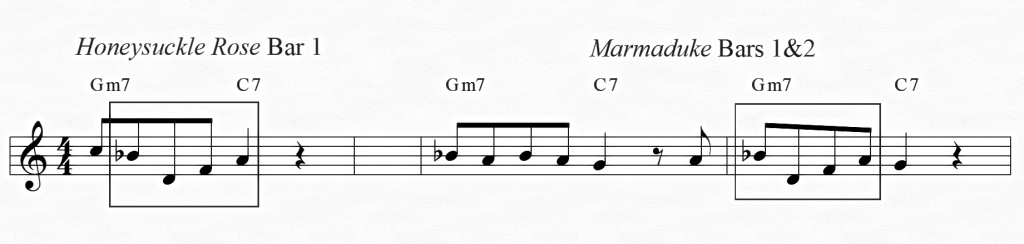

Honeysuckle Rose falls into this category, too, although it isn’t easy to put your finger on the 9th. Fats Waller’s composition stands out for being ahead of its time harmonically. II V progressions, as we know them today, didn’t exist in the 30s, yet the melody is a wheel of eighth notes on a roadway of repeating II Vs. This may have attracted Bird, as well.

I doubt anyone would dispute the importance of Honeysuckle Rose. Up A Lazy River is another story, since there’s no evidence Bird ever performed it anywhere, anytime. He didn’t even quote from it. In some ways, though, it’s a richer source of theoretic principles, and there are 9ths on every corner.

The fact that Bird quoted Honeysuckle Rose from time to time isn’t proof of anything, given his cage-free menagerie of quotes. Unlike most quotes, though, he didn’t just mention it in passing; he integrated it into his vocabulary, often transposing it in the process.

This is plain to hear from day one. In Honey and Body, he quotes it four times in a row, in four different keys: #1: original (F), #2: up a half step (Gb), #3: down a half step (E), #4: down a whole step (Eb).

It’s worth noting that only #2 is an exact quote.

#1 is a paraphrase with an ending of its own.

#4 has two notes reversed. This became a common variation.

#3 is shifted late by half a beat, starting on the and-of-one.

Shifting phrases by half a beat makes unsyncopated melodies syncopated, and it was standard procedure for Bird. As it turns out, the shift in #3 is particularly consequential.

It’s worth noting that none of the four phrases above functions as a tritone substitution. It’s almost certain that Bird hadn’t yet developed this concept. By 1950, though, quoting Honeysuckle Rose a tritone away had become routine. One of the clearest examples can be found in Smoke Gets In Your Eyes, from Bird at St. Nick’s, where he uses it twice.

He also uses it in I Cover The Waterfront with two notes reversed, as in #4.

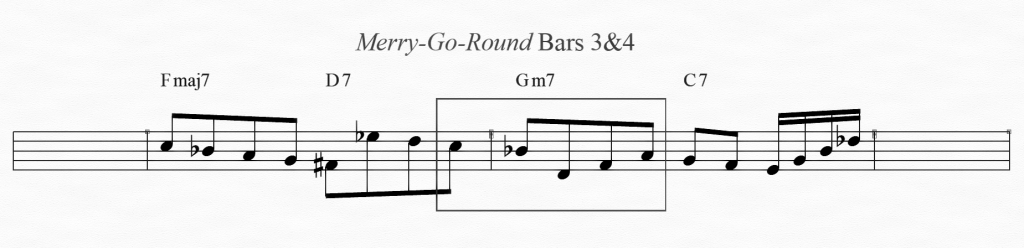

We will now turn briefly to Marmaduke. Eventually, we will look at all four tunes recorded that day (9/24/48). The other three are: Steeplechase (I Got Rhythm), Merry-Go-Round (I Got Rhythm with Honeysuckle Rose bridge), and Perhaps, the only blues recorded that day. (Bird usually recorded two blues at Savoy sessions.)

Again, Marmaduke is based on Honeysuckle Rose. At first hearing, it seems to make no reference to the original melody, which isn’t a surprise; most contrafacts chuck the melody and never look back.

But it’s there, shifted by half a beat.

Granted, it’s missing the first note, and has an extra note at the end. The missing note is specific to this particular composition. In most other contexts, Bird uses the first note as a pickup, as he does more than once on Merry-Go-Round.

Having shifted the phrase by half a beat, the extra note (G) is needed to resolve it. This final note is consistent throughout all variations.

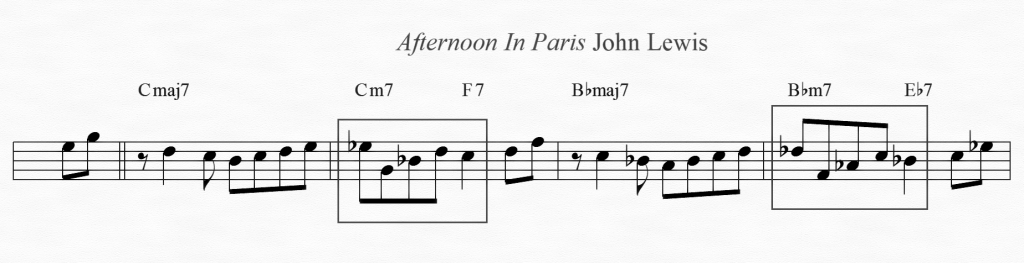

So the shift obscured the origins of this familiar bit of vocabulary. Miles used it in Donna Lee, and John Lewis appropriated it for Afternoon In Paris. (He’s playing piano on the Marmaduke date.)

Speaking of pianists, Bud Powell began using Honeysuckle Rose as a tritone substitution around 1950. It’s woven so deeply into his vocabulary that it’s conceivable he originated it, but the tune held no special meaning for him. Like so much of his vocabulary, he absorbed it from Bird and transformed it into something entirely personal and equally brilliant.

Here’s Bud playing Ornithology at Birdland, in May 1950, on that legendary night with Bird and Fats Navarro. He uses the Honeysuckle Rose variation four times!

We close with a mystery. The opening motif in bars 3 and 4 of Tadd Dameron’s Lady Bird is Honeysuckle Rose verbatim. There are reports that Tadd wrote Lady Bird in 1939. If so, it was written before he met Bird in Kansas City, in 1940. On the other hand, it wasn’t recorded until 1948, and there’s no way of knowing how much it changed in the interim. It’s certainly possible that Honeysuckle Rose inspired Tadd directly, without Bird’s involvement. But the title suggests otherwise.

Next time: Lazy Bird

NOTE: The case that Honeysuckle Rose and Lazy River contributed much to Bird’s vocabulary is laid out in detail, with notated examples, in the Parkeology Hypothesis, on the menu at the top of the homepage.

Bird Lives.

LikeLike