Parkeology 001: Bird Is In the Details

“You can tell the history of jazz in four words: Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker.” – Miles Davis

Or, if you’re not into the whole brevity thing, six words: Louis Armstrong, Lester Young, Charlie Parker.

The Lester-to-Bird connection is plain to hear. The Louis-to-Lester connection is largely a matter of faith. The search for Lester’s influences is so futile that in the end you just throw up your hands and say: who wasn’t influenced by Louis Armstrong?

A direct Louis-to-Bird connection might seem unlikely, but it turns out there’s a link via the West End Blues opening cadenza (Hot Five 1928).

Bird started quoting this famous opening around 1949. Most of his quotes have a storied history, but not this one. Here is the Armstrong cadenza itself, followed by two Bird quotes, one on Christmas Eve, 1949 (Cheryl, 1949 Concert), and the other from February 18th, 1950 (Visa, Bird at St. Nick’s):

Some claim that Bird didn’t discover West End Blues until 1949, and that his newfound admiration for Louis inspired him to quote from it. I find this hard to believe, given Bird’s deep awareness of all that came before, plus we are talking about one of the most celebrated recordings in jazz history, both in its day and for the ages.

More to the point, there’s direct evidence that the West End Blues cadenza was known to young Bird, and influenced his conception. This evidence is found in one of his first solos, recorded with Jay McShann on December 2nd, 1940, when Bird was twenty.

The tune is Honeysuckle Rose, and Bird opens with Lester’s motif from the Basie recording, acknowledging his debt. This was likely intentional, because he opens his Lady Be Good solo with another clear acknowledgement.

Here is Bird’s Honeysuckle Rose solo in full, preceded by Lester’s opening phrase from the Basie recording:

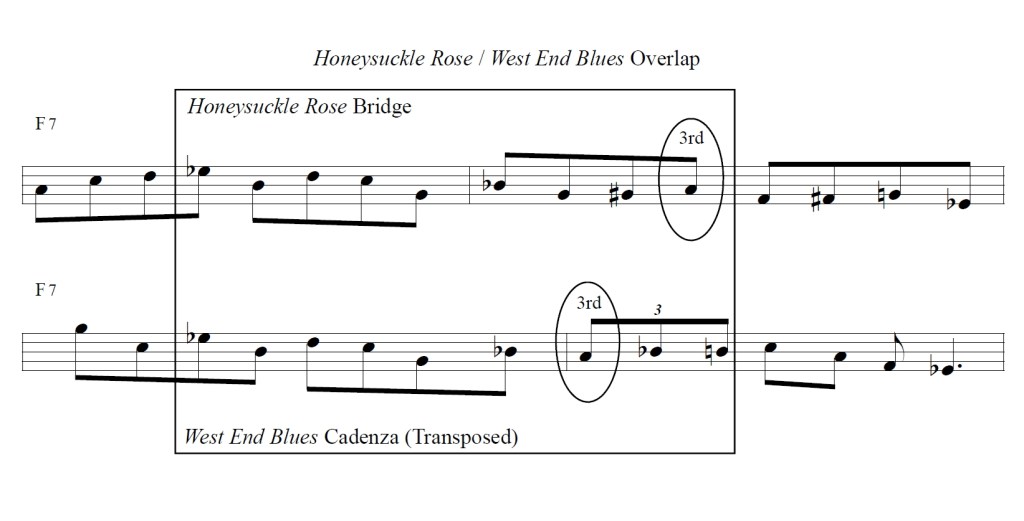

The connection to West End Blues can be found in the first bar of the bridge. The tempo here is quite fast (small matter for Bird, even at twenty) so you have to slow it down to hear it.

The following clip alternates between Louis and Bird, slowing down the excerpts and zeroing in on a six-note group that overlaps exactly, once you transpose Louis into Bird’s key.

They share a seventh note, the A, as well, but it doesn’t overlap. Louis proceeds right to it, while Bird comes at it chromatically from below, arriving a beat and a half later, but they both land on this pitch to resolve to the F7.

Here’s what it looks like on the page: (Note that Bird has shifted Louis’s phrase over by half a beat!)

These seven notes can be written off as coincidence if you’re so inclined, and we’re not here to argue. But it’s not just the notes that overlap, it’s the conception.

Both Louis and Bird are implying a C minor tonality on top of the F7, which they both resolve by landing on the A. I refer to this as building from the 5th, and in many instances Lester does the same thing.

But Parkeology isn’t a platform for pontification. The idea is to examine the countless intriguing fragments Bird left behind, fragments beneath the notice of jazz writers but of interest to Bird enthusiasts.

Bird is in the details.

Next time: Everything Goes Wrong