Parkeology 010: Past Due

If you play a track like, the difference in before he went in and the thing that he did after he came out, like Cheers and Carvin’ The Bird and so forth, this was a different man all completely from the way he sounded before he went in. – Howard McGhee (Interview WKCR)

Dean Benedetti recorded Bird every night for two weeks in a row, from March 1 through 13, 1947, at the Hi-De-Ho Club in Los Angeles. This level of documentation was unprecedented in its day, and it’s hard to think of a comparable example, even now. Thanks to Dean’s efforts, we can follow Bird as he works out new concepts on the bandstand in real time.

And Bird had a lot to work out. He’d recently been released from Camarillo State Hospital, where he’d been incarcerated for five months, from August 1946 through January 1947. Before-and-after comparisons show that his conception continued to evolve, even while locked away (see Parkeology 004).

We also have McGhee‘s testimony, and you couldn’t ask for a more credible witness. He did everything humanly possible to help Bird in Los Angeles, before and after Camarillo. He was also a first rate trumpet player and early modernist, well qualified to assess Bird’s development. And he was standing next to Bird at the Hi-De-Ho every night.

In describing “Relaxin’ At Camarillo,” Bird’s first composition after his release, McGhee says, “It’s syncopated so differently… The syncopation comes off the beat.” He seems to be saying that ordinary syncopation is felt against the downbeats, whereas Bird’s new syncopation was felt against the upbeats.

It was a new way of feeling time, impossible to put into words, but it’s plain to hear if you listen for it. Compare the studio version of “Yardbird Suite” March 3, 1946 (before Camarillo), with the Hi-De-Ho version, March 2, 1947 (after Camarillo).

The studio solo is certainly syncopated, but the phrases are anchored to the downbeats and centered around the bar lines. The Hi-De-Ho solo is more intricate and asymmetrical. It sounds to me as though Bird is consciously trying to skirt downbeats and defy bar lines. It’s a daring solo, beyond what he’d been willing to risk in his Dial studio dates (February 19 & February 28, 1947).

Bird didn’t return to New York, his adopted home, immediately following his release from Camarillo. Instead, he remained in LA for another two months, working as a sideman for McGhee at the Hi-De-Ho Club. It’s possible he delayed his return in order to work through the concepts that had come to him over the course of his confinement.

There is evidence to support this idea: Bird plays two new figures incessantly at the Hi-De-Ho, figures he seems to discard by the end of the two-week run. To the best of my knowledge–with one exception–they are nowhere to be found in any subsequent recordings, live or studio, for the remainder of his career.

Bird always uses Figure 1 as a phrase ending. It’s a drop from the major 3rd down to the 5th, then up chromatically to #5 and then 6, where it comes to rest.

Figure 1 made its first appearance, almost as a premonition, three days before the Hi-De-Ho gig began. Bird uses it in the improvised bridge to “Cheers,” (Dial February 26, 1947), as heard here.

Figure 1 is heard again two years later, like a distant echo, on “Cardboard” (Verve, March 5, 1949). From there, as far as I can tell, it proceeds directly into oblivion.

But Figure 1 had a good run at the Hi-De-Ho! Bird uses it in almost every solo. I stopped at twelve examples, many from March 7th alone, but I could have kept going indefinitely.

Bird uses Figure 1 in multiple keys and tempos. He seems to be deploying it at every opportunity.

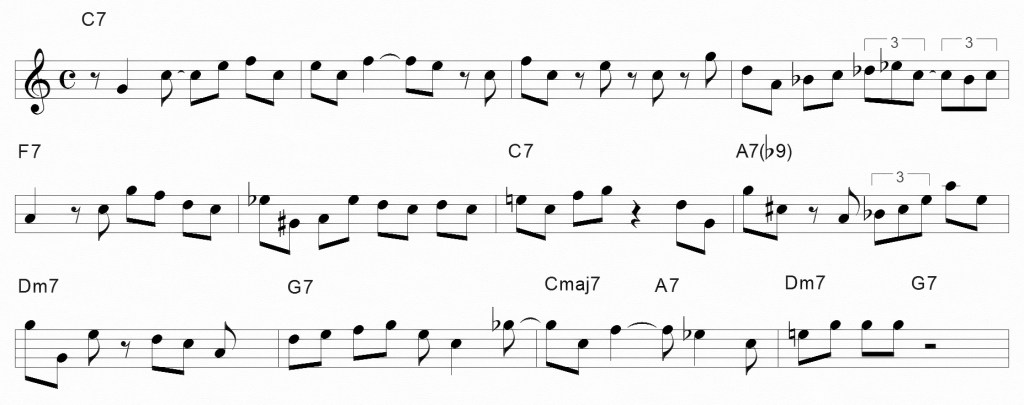

Figure 2 is the antithesis of Figure 1, existing in one specific location and one specific key. Bird only uses it in the third bar of the “I Got Rhythm” bridge, and only in the standard key of B-flat.

It’s another simple phrase ending which exists on dominant 7th chords: b7-1-b9-1. Bird tends to start it on beat 3, as notated, but he also starts it on beat 1.

It’s no surprise that B-flat rhythm changes came up a lot at the Hi-De-Ho. “Moose The Mooche” and “Wee” were both in the rotation. And another standby, “Perdido,” also in B-flat, has an “I Got Rhythm” bridge.

The following Figure 2 examples, culled from several nights, are found in “Moose The Mooche” and “Perdido.”

This example comes from a single performance of “Perdido.” Bird uses Figure 2 on all three bridges!

Bird uses Figure 2 just as frequently in “Wee.”

In these “Wee” examples, Bird seems to be trying out alternatives, substituting the major 9th for the minor 9th.

He leads into Figure 2 with the same motif each time, and something similar precedes Figure 2 in all examples. Was he working on that motif, as well?

All in all, Figures 1 and 2 raise more questions than they answer.

Do they represent a general working method, a practice of integrating new motifs through repetition? Was Bird even conscious of this process? Did he use this approach at other points in his development? What made him single out these particular figures? And why, after two weeks of test driving them, did he end up scrapping them?

All we can do is guess.

The Hi-De-Ho recordings are an inexhaustible resource, and further study will produce more unanswerable questions, but that’s just the way it is.

When it comes to Bird, sometimes questions are the only answers we have.