Parkeology 018: Brute Force

Still, one is brought up short by the realization that a “typical” Parker phase turns out to be much the same phrase one had heard years before from, say, Ben Webster. The secret is, of course, that Parker inflects, accents, and pronounces that phrase so differently that one simply may not recognize it. – Martin Williams

Williams seems to have picked Ben Webster’s name out of a hat, but there may be a deeper connection than he realized. Webster’s chromatic motifs might have added a missing component to Bird’s conception in the early 1940s.

When I say chromatic motifs, I’m talking about consecutive half steps in a melodic line. By that definition, Bird used few chromatic motifs during his period with Jay McShann (1940-42), aside from connecting two diatonic notes together.

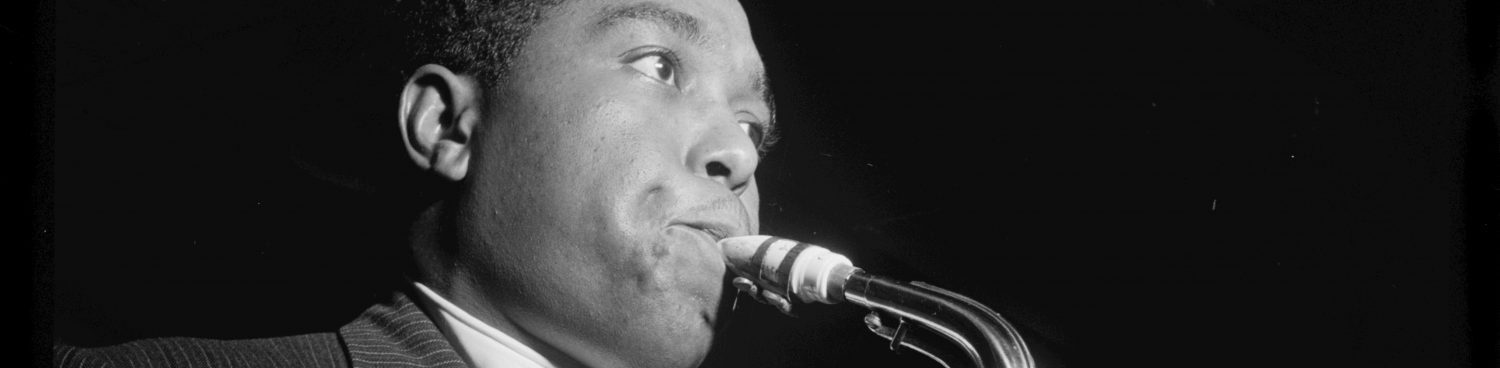

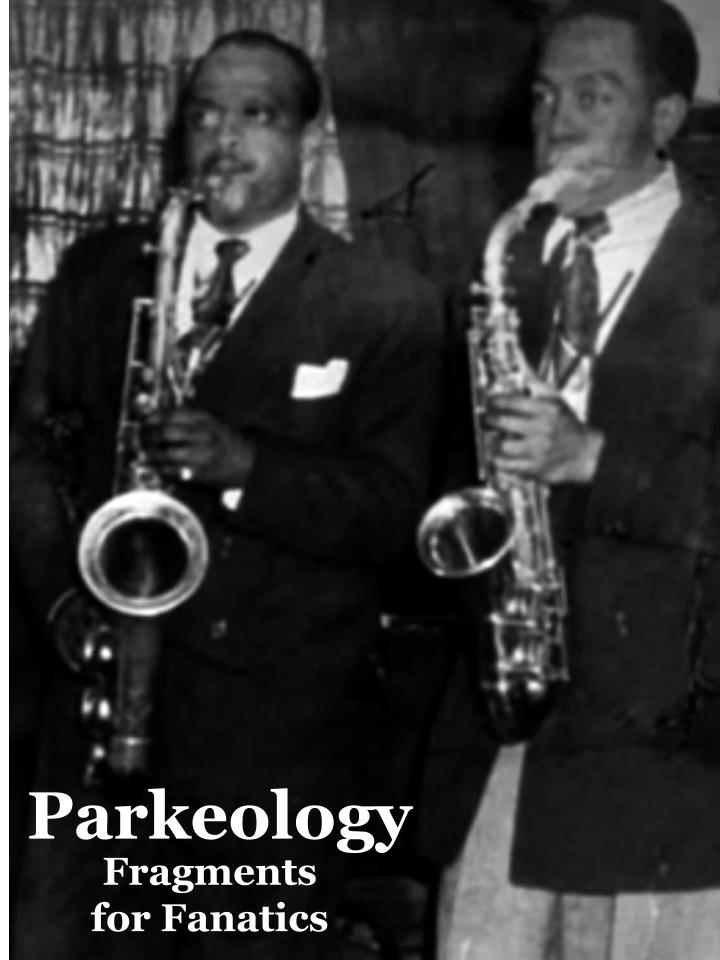

This began to change in 1943, as evidenced by the Redcross recordings from February 15. Bird became a tenor player when he joined the Earl Hines Orchestra in December 1942, and he’s playing tenor on these no-fi hotel room recordings. They add a great deal to our understanding of Bird’s development, while also revealing his remarkable grasp of the tenor saxophone tradition. He can sound, at will, exactly like Hawkins, Webster, or Lester.

Ben Webster isn’t thought of as an innovator, likely due to bad timing. His melodic and rhythmic advances, different from Hawkins’, gathered steam in the late 1930s and culminated during his stay with Ellington, in the early 40s. This was good timing for Bird, who was at a crucial juncture in his development, but Webster’s contributions were quickly swept downstream by the bebop revolution. What’s more, Lester Young’s ascendance made Webster’s Hawkins-based tone sound outdated, even though his ideas were new.

“Cotton Tail” (May 1940) seems to have influenced Bird directly, not just Webster’s 64-bar solo but the saxophone soli, as well, which some say Webster wrote. Let’s give “Cotton Tail” its props as the most prescient big band chart ever written, three minutes and thirteen seconds of pure joy, doubling as a roadmap to the future:

A great unknown hovers over this thesis: when did Bird first hear “Cotton Tail?” As with all unknowns, we don’t know. He was probably aware of it when it first came out, but fellow Bird enthusiast Jay Brandford (Symphonic Sidney), suggests that the recording might have taken on new importance when Bird began playing tenor (ditto Lester’s “Shoe Shine Boy”). This would explain why Webster’s chromatic motifs don’t enter Bird’s vocabulary until 1943.

We know Bird knew “Cotton Tail” because he quotes it on the Redcross recordings, both the theme and the bridge from the saxophone soli. On “Three Guesses,” he quotes the first four bars of the bridge (1:50), followed by his own variation:

On “Yardin’ with Yard,” he quotes theme and bridge, using them as background lines behind the trumpet solo. The excerpt below starts with the bridge (3:31), which Bird quotes in its entirety, followed by the theme:

Until recently, I had been out to lunch concerning the “Cotton Tail” recording date, which I vaguely placed around 1943. As a result, I didn’t make much of the chromatic motif in Webster’s solo, which became a mainstay of Bird’s vocabulary. In 1943, the zeitgeist was such that I thought Webster might have even picked it up from Bird, at Minton’s or Monroe’s. But the 1940 recording date changes everything. It was a one way street, Webster to Bird.

Here’s Webster’s chromatic motif (slowed down for clarity):

Bird uses it for the first time (on record) in his solo on “Yardin’ with Yard,” at 1:14 (slowed down for clarity):

It should be noted that certain fundamental building blocks in young Bird’s vocabulary were actually quotes, “Honeysuckle Rose” being the prime example (Parkeology 005). I believe this is also the case here.

Webster’s chromatic motif appears throughout Bird’s career. A brief survey of 1947 Dial recordings yields three examples, from “Bongo Bop” Take A, “Bird Feathers,” and “Klacktoveesedstene” Take B:

This motif is equally common on Bird’s Savoy recordings from September 1948. Here are three examples, from “Barbados” Take 1, “Ah Leu Cha” Take 2, and “Perhaps” Take 3:

Webster had many other chromatic ideas worthy of consideration, but this was the most consequential. He deduced that the magic number of half steps was five, timely information for young Bird, whose conception was still solidifying.

There’s a lot to pursue here, but this post has gone on long enough, so I will close with a preview (slowed down for clarity). Webster plays a phrase in “Linger Awhile” (November 7, 1940) that appears in Bird’s solo on “Scrapple From The Apple” Take C (and in many other solos). I have transposed Bird’s phrase down a whole step so it matches Webster’s key:

Those who doubt the Webster connection might argue that Bird was surrounded by influential saxophonists of every description, with Webster somewhere on the outskirts of this throng. What possible reason would Bird have had to single him out for study?

How about this: they were both born and raised in Kansas City.