Parkeology 019: Native Son

John Fitch: Whom do you feel were the really important persons, besides yourself, who started to experiment?

Charlie Parker: Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Kenny Clarke. It was Charlie Christian… There was Bud Powell, Don Byas, Ben Webster, yours truly.

– 1953 radio interview WHDH

I think it’s significant that Bird includes Ben Webster in this list, because Webster isn’t remembered as a modern jazz innovator, despite his involvement at Minton’s. Note that Bird lists their names together, at the bottom. In my opinion, he’s acknowledging Webster’s influence on his own conception more than on the movement in general.

It’s my theory that Webster’s chromatic motifs added a missing component to Bird’s conception in the early 1940s. As noted in Parkeology 018, when I say chromatic motifs, I’m talking about consecutive half steps in a melodic line.

In order to make my case, a timeline is necessary, but it comes with a disclaimer. Since first posting this column, I discovered that Webster was on the road with the Duke Ellington Orchestra for all of 1941 and 1942, spending almost no time at all in New York City. In 1942, the year these anecdotes purportedly take place, the Ellington band was only in NYC for one day, for a recording session! This paradox is worthy of its own post in the not-too-distant future. For now, onward to the timeline.

Bird and Webster were both born and raised in Kansas City, but Bird was eleven years younger, so it’s unlikely they ever met there. Webster was working locally with Andy Kirk in 1933, but in 1934 he joined Fletcher Henderson’s band and adopted New York City as his home. Bird would have been fourteen then, just getting serious about music.

Despite his departure, Webster was still Kansas City’s native son, and Bird would go on to work with many musicians who knew him and had played with him. This, I believe, drew his attention to Webster’s music, which might not have happened otherwise.

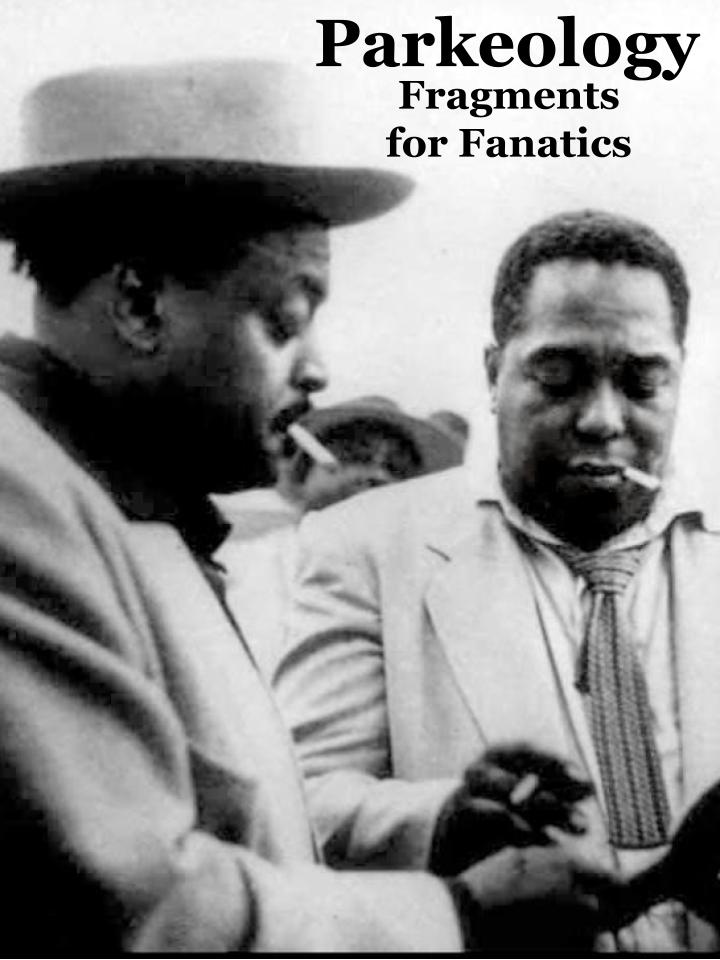

We know Bird and Webster met in New York City, the only question is when. This is important because Bird, until then, would have only heard Webster on record. Once they met at Minton’s and/or Monroe’s, we can assume they went on to jam together there, at which point Webster would have begun influencing Bird in person.

There are two contradictory anecdotes about their first meeting. The earlier of the two, accepted date winter/spring 1942, takes place at Monroe’s Uptown House. Webster describes it in an interview with John Shaw:

There was this guy on the stand blowing this weird stuff. It was Charlie. I said to Clark [Monroe] “Is that cat playing what I think he’s playing?” I was feeling pretty fit, but I didn’t trust my ears.

The second anecdote takes place at Minton’s and comes from Billy Eckstine:

Charlie’s up on the stand and he’s wailing the tenor. Ben had never heard Bird, you know, and he says, “What the hell is that up there? Man, is that cat crazy?” And he goes up and snatches the horn out of Bird’s hands, saying, “That horn ain’t supposed to sound that fast.” But that night, Ben walked all over town telling everyone, “Man, I heard a guy—I swear he’s going to make everybody crazy on tenor.”

This couldn’t have happened any earlier than December 1942, when Bird joined the Earl Hines Orchestra and switched to tenor.

In his own account, Webster says nothing about Bird playing tenor. There’s no mention of it in the Les Tomkins interview, either. Webster simply says:

New York was really the place to be, with guys around like Hawk, Don Byas, Chu, Pres, Herschel Evans, Ike Quebec. And I heard Charlie Parker for the first time and that was quite a thrill. This guy scared me to death!

Jay McShann sows further doubt by claiming that Webster first heard Bird in February 1942, when his orchestra made its debut at the Savoy Ballroom:

When we got to New York, Ben Webster went down and told all the saxophone players down on 52nd Street, he said, “All you guys who think you can play saxophone, you’d better go up there and there’s this little saxophone player up there with Jay McShann’s band, a new band in town from Kansas City. All you guys better go up there and go to school.”

Allowing for poetic license, McShann’s account doesn’t contradict Webster’s, but it doesn’t help pin down the date, either. In truth, their meeting at Monroe’s could have happened at any number of points in 1942. The McShann Orchestra was in and out of New York all year, and Bird took a sabbatical in April/May, which he spent at Monroe’s, subsisting on tips.

If, however, Eckstine is to be believed, Bird began jamming with Webster at Minton’s shortly after he switched to tenor (12/42), making Webster a direct influence at a crucial juncture. I like this version because it buttresses my argument, but both anecdotes can’t be true, and I must take Webster’s word over Eckstine’s.

The Hines Orchestra rehearsed in New York throughout December 1942, then played a Christmas Day gig, a New Year’s Eve gig, and a one-week stint at the Apollo Theater, January 15–21, 1943. Webster probably encountered Bird playing tenor at Minton’s during this period, whether or not they had met before.

By January 22, though, the Hines band was in Baltimore, and they spent the next three months on tour. It was during their brief stay in Chicago that Bob Redcross recorded Bird and Diz in his room at the Savoy Hotel (February 15, 1943). These recordings provide compelling evidence of Webster’s influence on Bird.

Webster’s use of chromatic motifs developed gradually, but by the time he joined Ellington (1940) they could be found in most solos. Here’s a chronological pastiche, starting with “Congo Brava” (March 1940) and ending with “Main Stem” (June 1942):

By the time he left Ellington in August 1943, Webster was a star. He formed a quintet and found steady employment at the Three Deuces. This coincides with Bird’s departure from the Earl Hines Orchestra.

The following chromatic motifs come from radio transcriptions from September 1943. Eight numbers were recorded for broadcast (complete tracks below), all offering Webster, as leader, extensive solo space. It’s a safe bet that Bird never heard this broadcast nor the recordings made for it, but it documents Webster’s style at the moment of his peak influence, when he and Bird were jamming together at Minton’s/Monroe’s. Bird would have heard Webster play similar ideas in person:

By 1945, Bird had realized that Webster’s chromatic motifs could solve certain structural problems, but that’s a topic for another time. Instead, I will close with a Ben Webster quip.

Bird played in Webster’s band on 52nd Street for a short time in 1945. Between sets, Bird would take his horn and sit in at other clubs, and if he was having fun he wasn’t overly concerned about making it back for the next set. Jay McShann dropped by one night to hear Bird, who was nowhere to be seen. He asked Webster if Bird was on the job, and Webster replied:

“Yeah, he works for me, but he plays up the street.”

* * * * *

Here are the eight tracks from the September 1943 transcriptions (in the same order as the excerpts above): “Woke Up Clipped,” Teezol,” “The Horn,” “Don’t Blame Me,” “I Surrender Dear,” “Tea For Two,” “Dirty Deal,” and “‘Nuff Said.”

Personnel: Ben Webster, Hot Lips Page, Clyde Hart, Charlie Dayton, Denzil Best.