Background information on Thomas Owens and the origins of this project here: https://charlieparkercentennial.com/thomas-owens/

You can find both volumes of Owens’ original dissertation on the Internet Archive:

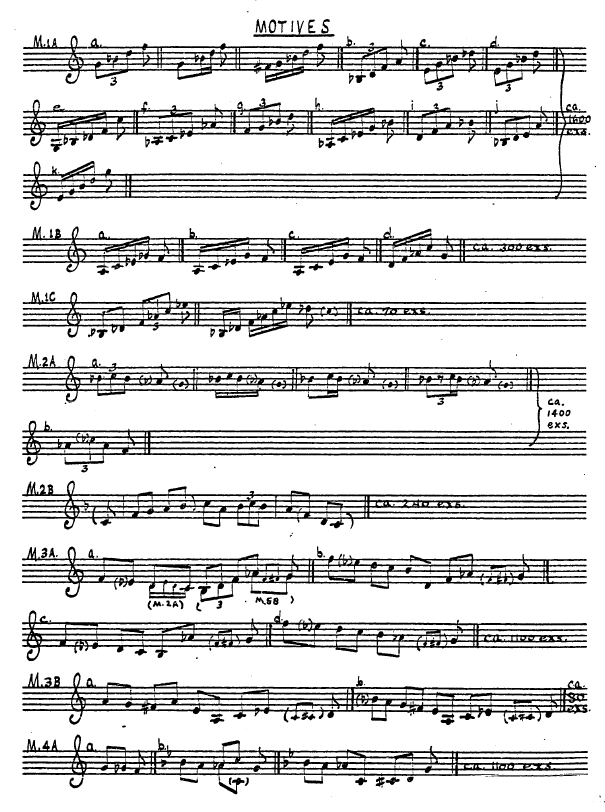

This page presents Thomas Owens’ 64 motives pitched in E-flat, as Bird played them on alto saxophone. In his dissertation, Owens notates these motives at concert pitch. This is understandable yet frustrating, since most motives are much too low to be played comfortably on saxophone. In our opinion, then, the first step in making his thesis more accessible was to transpose these motives into alto saxophone key, which we have done here.

It’s a big improvement. These motives are now easily recognizable to anyone who has studied Bird’s solos in E-flat, and they can make their own connections to passages in familiar solos.

But there is more to be done. After laying out his 64 motives, Owens proceeds to catalog them by key, starting with D-flat major and ending with G major. This makes a lot of sense, given that much of what Bird played depended on what key he was in. It would be well worth reproducing that catalog here.

One step, however, takes priority over everything else. Owens transcribed four solos and then dissected them, enclosing his motives in brackets wherever they occur. This is where the rubber meets the road, so to speak, and we will post these transcriptions in the near future, in E-flat.

In the meantime, here are Thomas Owens’ 64 motives in E-flat. The following text comes directly from Owens’ dissertation, unaltered except for key and note names, which have also been transposed to E-flat, to match the motives.

Two short motives, M.1A and M.2A, occur more frequently than any others. Each appears once every eight or nine measures, on the average, in the transcriptions.

M.1A is an ascending arpeggio, usually played as a triplet, but also common in other rhythmic configurations, as shown in M.lA a. Preceded by an upper or lower neighbor, it frequently begins a phrase; however, it may occur anywhere in the course of a phrase. About 40% of these arpeggios are of minor-seventh chords; E minor-seventh is the most common, perhaps, because notes in the C major scale are particularly easy on the alto saxophone. About 130 different ascending arpeggio’s appear in the transcriptions, mostly in the chord forms of M.lA abcd. Some of the more unusual forms are M.lA efghijk. The numerous varieties of M.1A all treat the highest note of the arpeggio as the goal of motion, reaching it on the beginning of a beat.

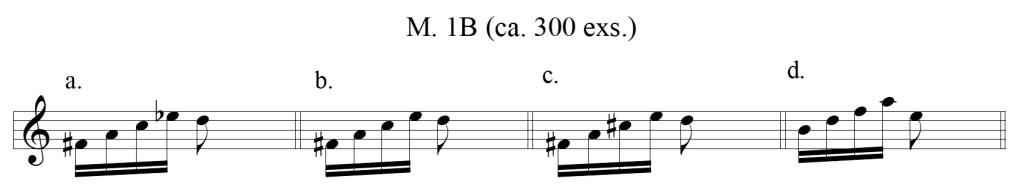

A related motive, M.IB, turns back on itself, reaching its goal immediately after the high note of the arpeggio. It occurs in about 80 different forms in the transcriptions, some of the more common of which are shown. While the final note is usually a second lower than the highest note, it is sometimes a third or fourth lower, as in M.1B d.

M.1C resembles both of the two preceding motives. But whereas M.1A and M.1B are nearly always seventh or ninth chords, M.1C is a complete eleventh chord of the type that occurs on the supertonic of a major key. Compared to the others in this group it is a rare motive, but its construction is distinctive enough to warrant separate mention.

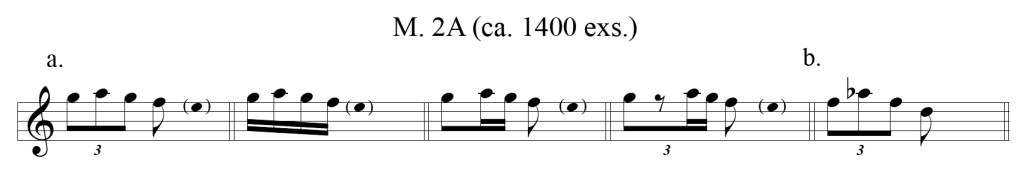

The other ubiquitous motive, M.2A, is even simpler in construction and easier to play than the ascending arpeggio. In its main form it is nothing more than an inverted mordent followed by a descent of a second, third, or fourth. In a few instances the initial minor or major second becomes enlarged, as in M.2A b. Because of its brevity and simplicity, the motive appears in virtually any context. Indeed, it is an incidental component in a number of more complex motives, as will be shown later.

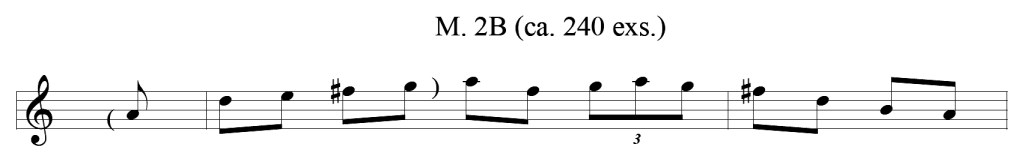

It is also a central feature of one longer motive, M.2B. Except for its last two notes this latter motive is identical to the first phrase of Parker’s melody “Ornithology.” Strangely, however, this motive usually appears in D major, and rarely appears in E major, the key of “Ornithology.” Perhaps the motive occurs primarily in D because the inverted mordent on G is an easy figure for the alto sax.

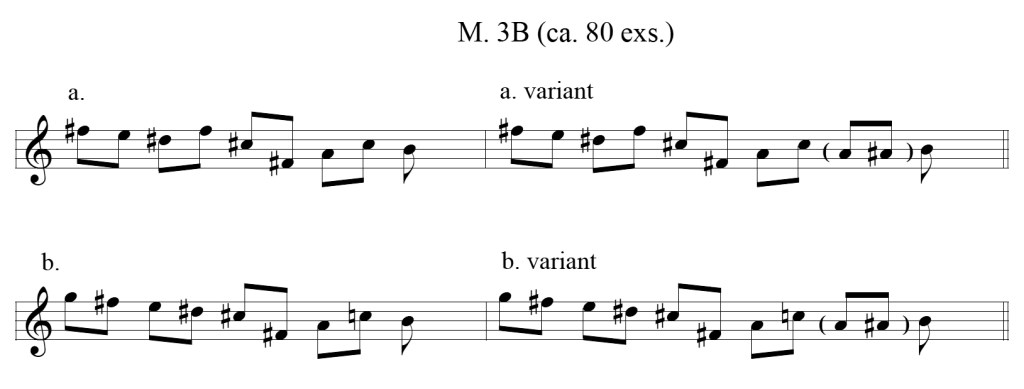

Ranking third in order of frequency is a more extended motive, M.3A. Its four main forms and several additional forms all have two notes in common: the third and the minor ninth of a primary or secondary dominant chord. M.3B, a closely related motive, differs from M.3A in two ways; it contains both the major ninth and minor ninth, and it occurs exclusively on a B dominant-ninth chord. Why it does not occur on a A ninth chord, where it is just as easy to play, is unexplainable.

Parker’s longer motives frequently incorporate shorter motives. For example, M.2A and M.1A often appear in M.3A, as shown. Further, all forms of M.3B often end with a chromatic encircling, produced by the parenthetical notes, giving rise to another motive, M.5B (discussed below).

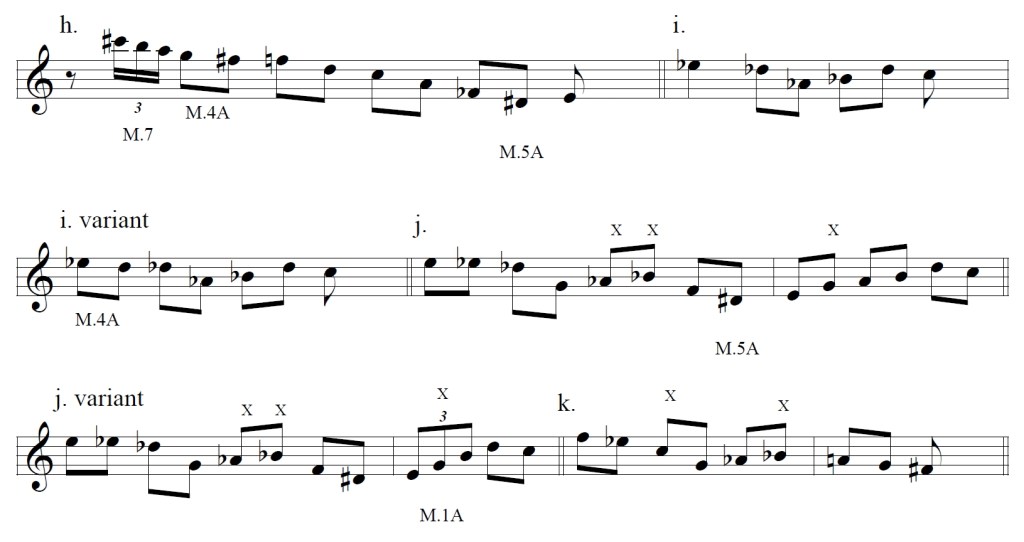

One of the simplest motives in this catalog is the three-note M.4A. Hardly distinctive to the casual listener, it usually appears in certain well-defined contexts. In most cases it occurs during the playing of the tonic chord, and moves from steps 2 to 1, 6 to 5, 5 to 4, or 8 to b7. These last two categories are related; 5 to 4 is motion into the seventh of a V7 chord, and 8 to b7 is motion into the seventh of a V7 of IV chord. Nearly all of the remaining examples fit one of these four categories, but superimposed on a secondary tonic, as in the second four measures of “How High the Moon”. Occasionally the motive is developed into longer forms, as shown in M.4Abc.

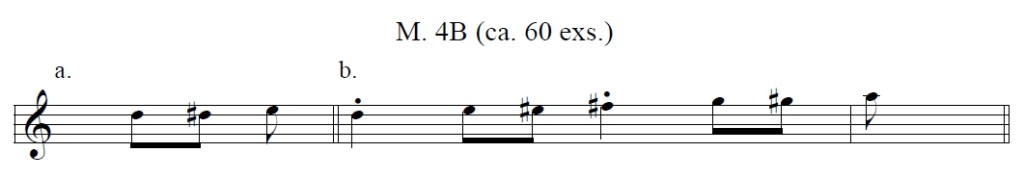

The inversion of M.4A gives rise to M.4B, which usually moves from 2 to 3 or from 4 to 5 in a chord.

Four chromatic scale tones played in the time occupied by M.4A produce M.4C, a filled-in minor third. Here again, an unimpressive figure fulfills certain limited functions; most examples rise to the second or fifth degrees of the scale. This selectivity is due partially to the construction of the major scale, for 7 to 9 (or 2) and 3 to 5 are minor thirds. Further, the rise from 7 to 9 leads smoothly into an effective cadential formula that occurs occasionally M.4Cb. But the intervals from 2 to 4 and from 6 to 8 are also minor thirds, and the filling of these intervals accounts for only about 12% of the total. Parker’s preference for two of the four possibilities defies rational explanation. M.4D, the inversion of M.4C, occurs only half as often in the transcriptions. Its patterns of usage are less clearly defined.

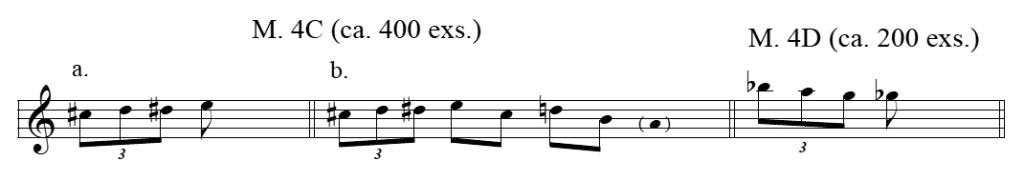

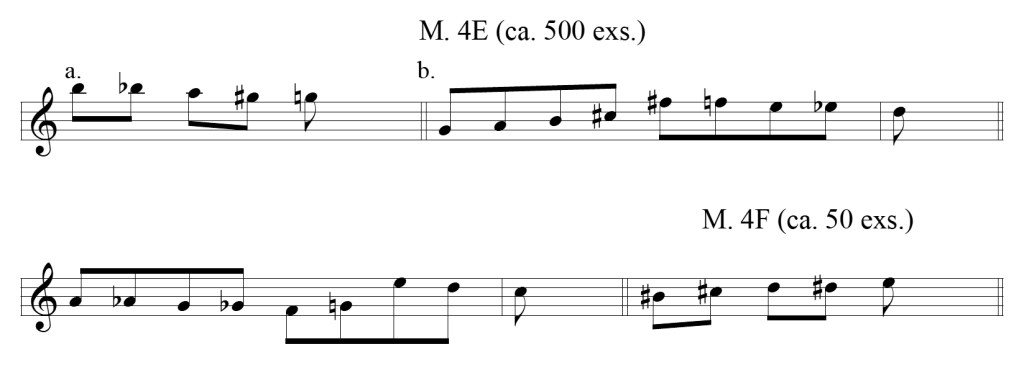

M.4E, a chromatic descent of a major third, is a further extension of M.4A. It occurs most often in descents to the fourth degree of the scale and to the tonic pitch. Both descents serve similar functions, for the descent to step 4 usually corresponds to a change of harmony from I to IV, as shown in M AEb. The inversion of M.4E, M.4F, occurs only one-tenth as often. It usually represents an ascent to the dominant pitch.

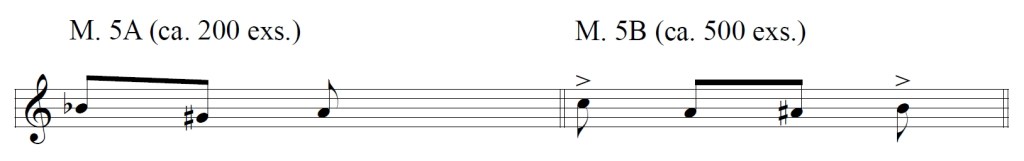

The next group of motives also involves chromatic motion, but these motives incorporate one or more changes of direction. The first, M.5A, is another seemingly unimpressive figure, which nonetheless fulfills a particular function. About half of the examples in the transcriptions encircle the fifth of a chord. Probably because the motion B-flat to B is technically easy, the example shown is on Parker’s favorite pitch level for this motive. M.5B is a one-note extension of M.5A, used most often to converge on the third of a major triad. About 40% of the time, the note is B and the triad is G major, as shown. The motive is often part of a larger pattern, M.3A.

A further extension of this chromaticism, M. 5C, occurs in ii7 to V7 harmonic contexts. Often preceded by Parker’s favorite ascending arpeggio, M.lAa, it consists of two overlapping statements of M.5B, the first of which is displaced by half a beat. It almost always occurs on the pitch level shown, that is, when the pitch center is D. M.5Cb is a shortened form, and M.5Cc is a similarly shortened form with a larger initial interval.

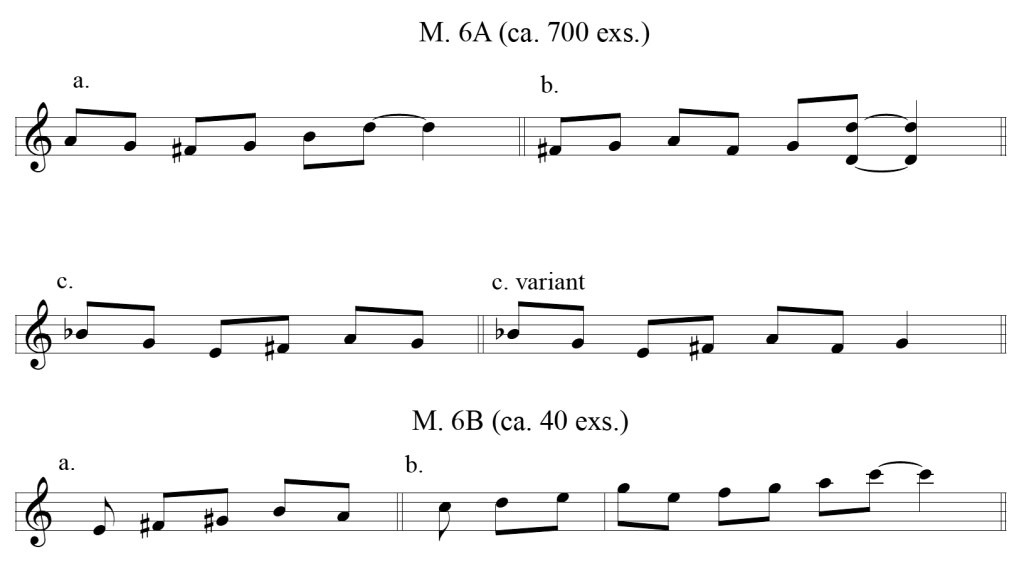

The chromaticism of the last two groups of motives contrasts sharply with the diatonicism of the next group. M.6A usually occurs as a cadential formula that encircles the tonic pitch in one of several ways. Nearly all tones serve as the pitch center for these figures, although M.6Ac almost always occurs in G. M.6B is not a cadential formula, but contains a similar encircling of pitch centers.

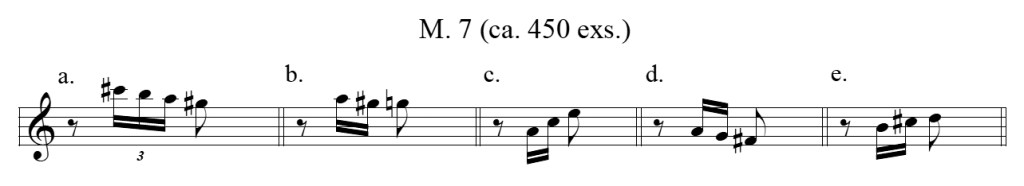

The phrase that is brought to a close by M.6A might well begin with the next motive, M.7. It consists of a simple two-or three-note flurry leading into the first important note of the phrase. The transcriptions contain about 140 varieties on all pitches; no clear preferences emerge as to either shape or direction. Some examples are actually M.4A or M.4B in diminution, but are included here because they function distinctively as phrase incipits.

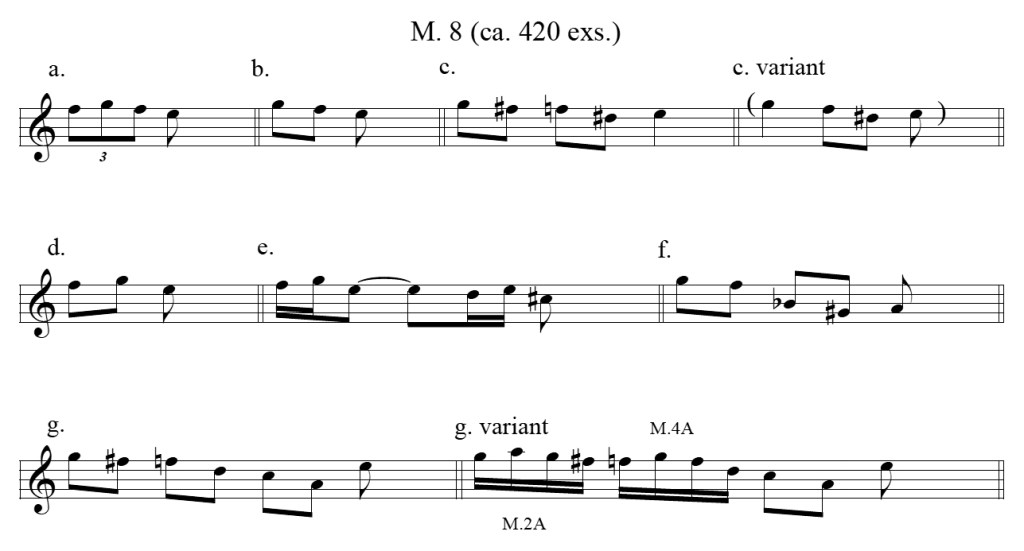

In contrast to the simplicity of M.7, the next group contains several inventively complex melodic patterns. The common feature of these figures is motion into the dominant via b7 and b6. Since more than 95% of Parker’s repertory is in the major mode, these notes are nearly always borrowed from the parallel minor mode. The most frequent short motives of this type appear in M. 8abcdef. They appear in a variety of keys. Decorated forms of M.8b and M.8c appear in M.8ghi. In these, b3 of the minor mode is also borrowed. These phrases, in contrast to the first five simple phrases, are absolutely linked to the keys shown, probably because they are easy to play in these keys. Finally, the last two phrases, while containing the basic elements of this group (indicated by Xs), begin with notes that are borrowed from C and D Phrygian. Phrygian borrowings to build harmonies were common in jazz years before Parker began to record; he probably had sonorities used by Duke Ellington and others in mind when he formulated these phrases. This same Phrygian borrowing can explain all of the M. 8 motives, although the absence of the lowered second scale degree in most of them makes such an explanation unnecessary.

M .9 is another complex motive that appears in several varieties. It fits a specific harmonic context, iii7 – biii7 – ii7, and occurs most commonly in measures 8 and 9 of the blues. Shown only in G, it occurs in all the important major keys in Parker’s repertory. It is absent from minor-key contexts because the construction of the minor mode prohibits such a progression.

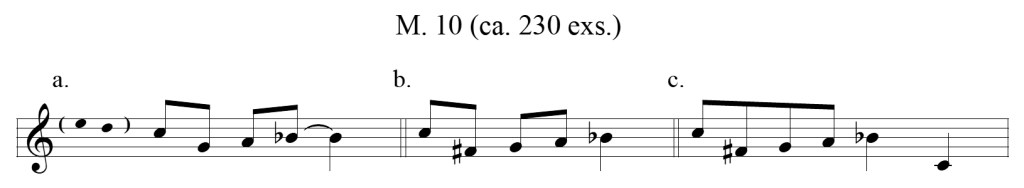

M.10 is specifically associated with dominant seventh chords, especially IVb7 which occurs in measures 5 and 6 of the blues. Its most common form is M.10a.

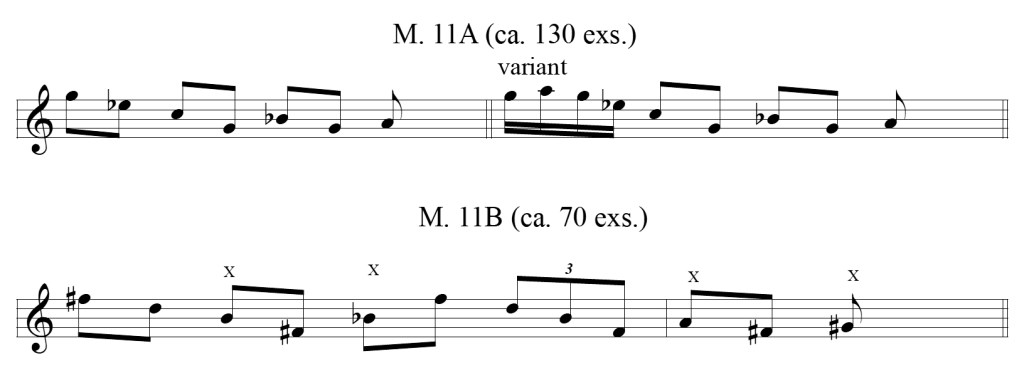

M.11A is a phrase for moving from ii7 to V7 in a major tonality. It usually appears in one of three keys, G, A, and B-flat. M.11B takes a variety of forms, but always contains the chromatic descent indicated by Xs.

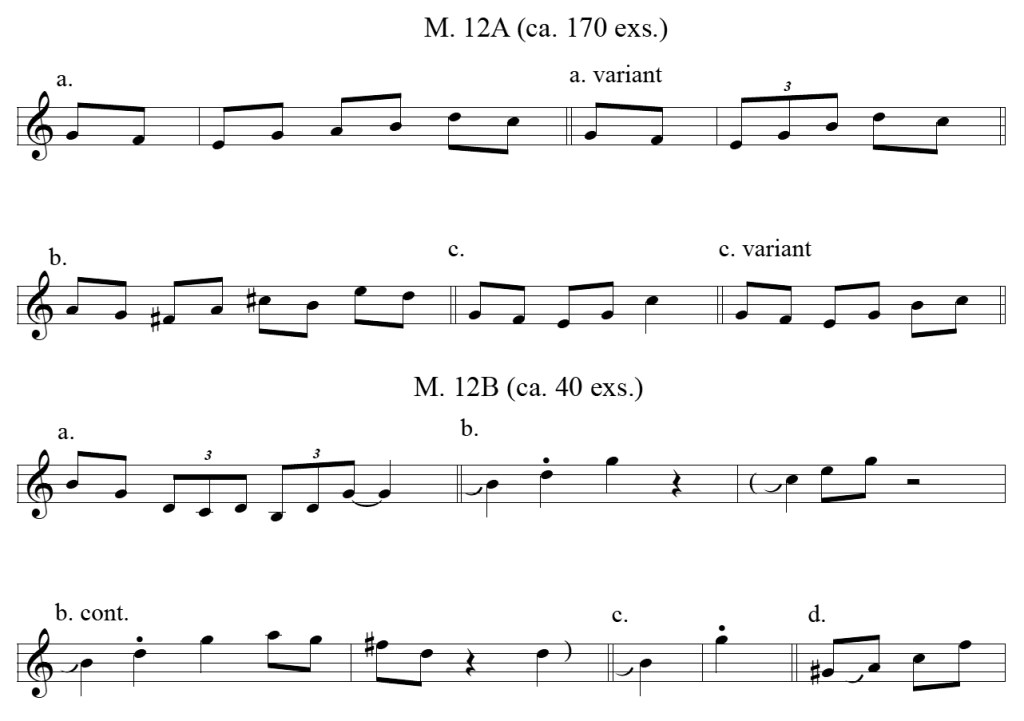

The figures of M.12A, with their motion through the notes of a triad, usually occur at or near phrase endings. They generally occur in moderate to fast tempos, on C and D major chords. M.12Ba is closely related and also serves a cadential function, but is limited to the end of the first phrase of a slow blues chorus in G. M.12Bb and M.12Bd again move through the notes of the tonic chord, but are generally phrase incipits. M.12Bc, a rare figure, appears only at beginnings of blues choruses in G.

The next group of motives involves descending arpeggios on the supertonic. They occur in two forms, half-diminished seventh and major seventh. Both motives are clearly associated with specific roots. M.13A usually appears as a A half-diminished seventh, in the context of G major (ii dim7) or B-flat major (vii dim7). M.13B appears only as b2 in G, where it’s easy to play. It is also easy to play a tone higher, but Parker ignored that possibility.

M.14A serves as a musical prefix to M.12A, and also appears independently. It occurs primarily in C and D, as does M.12A. The last three notes of M.14A a and M. 14A b closely resemble M.5A. Because Parker tended to play the G or G# in these figures softly, it is often impossible to hear with certainty which note was actually used.

M.14B has a similar shape to its predecessor, but the harmonic context is different; it occurs only on V7 of V in G and F. M.14C and M.14D are relatively rare motives that share the descending arpeggio with the other motives of this group.

The main element of M.15 is a downward portamento of approximately a half step. The second note is usually not fingered, but is simply the end of the portamento, which is produced by lipping down. Strangely, the most common portamento, D to C#, is more difficult to produce than others that Parker avoided. Usually the portamento is an embellishment of a larger motive, as indicated in M.15bcd.

Some writers on jazz have made much of bop musicians’ use of the diminished fifth scale degree. With the advent of bop, this note supposedly became as common as the minor third and minor seventh scale degrees, the other blue notes. The evidence suggests that, at least in Parker’s case, the importance of blue notes has been overstressed. His application of the traditional “blue third” is rare, and he never used the “blue seventh” except when it functioned as the blue third of a dominant chord. Only the “blue fifth” occurs often enough to be included in this discussion of his most common motives, and among this group it is comparatively rare. However, he tended to play it in an attention-drawing way, which may explain earlier writers’ preoccupation with it.

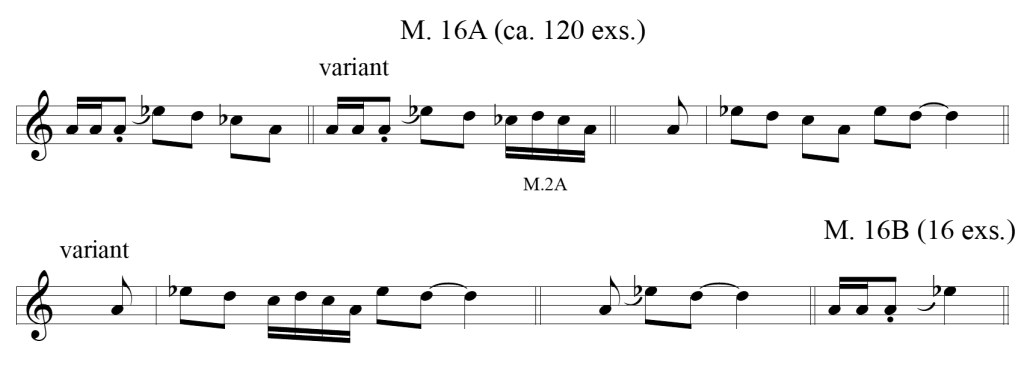

M.16A shows some of the contexts in which the diminished fifth appears (transposed to A for purposes of comparison). It appears in all the major keys from B-flat through E, and in some minor keys, but is most common in D major. The machine-gun-like incipit of M.16Aa usually follows a pause of several beats, so the motive attracts the listener’s attention immediately. Sometimes the short notes precede a portamento into the blue third rather than the blue fifth, as shown in M.16B.

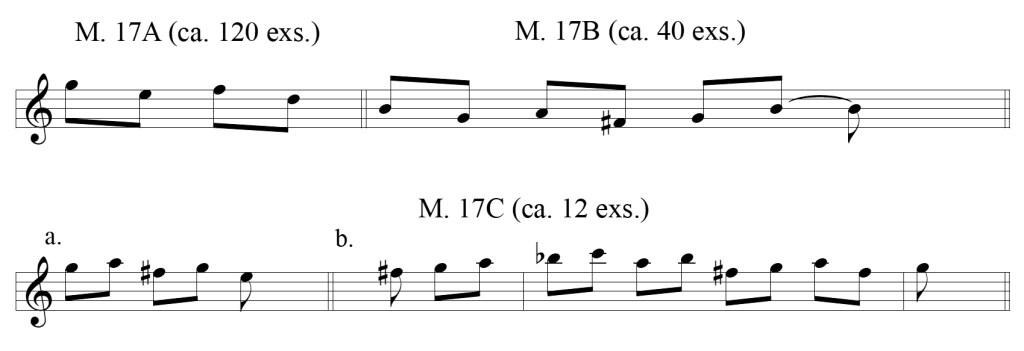

The last of the frequently-encountered motives, M.17A, generally occurs at the end of a phrase. An extension of this motive, M.17B, serves as a cadential figure, and appears only in G, F#, and F. Finally, M.17C changes the falling-third, rising-second pattern of M.17A into a rising-second, falling-third pattern.

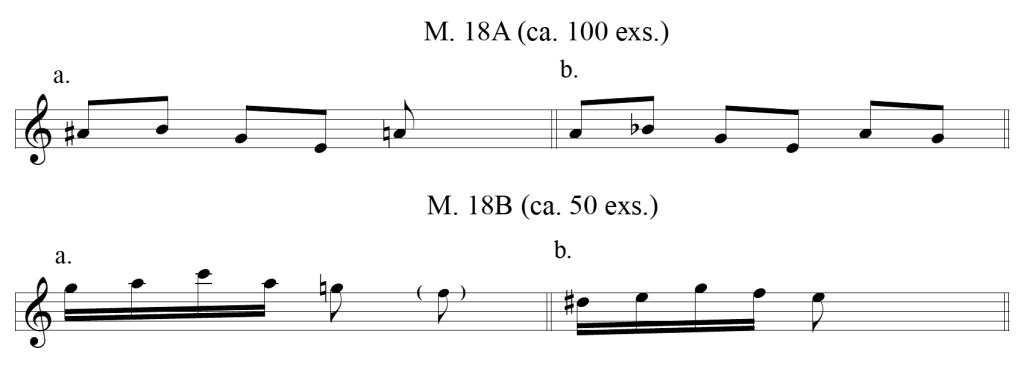

M.1 through M.17 constitute the great majority of repeated motives, but a large number of relatively rare motives, number M.18 through M.64, also appear in the transcriptions. Some appear so rarely that their inclusion in this list might seem unnecessary. However, they are included here for one or more of these reasons: 1) they are aurally striking when they do occur; 2) they appear several more times in untranscribed pieces; or 3) they are a characteristic of one particular key or group of pieces. All are shown at their most characteristic pitch levels. Pertinent remarks on selected motives follow:

M.19ABC – lipping up to any note is technically easy.

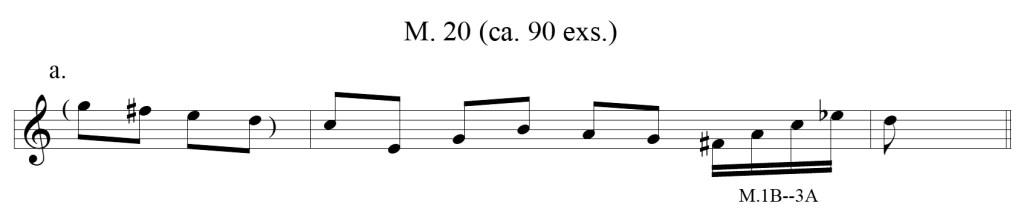

M.20 – almost always found in G, probably because the G scale is easy, as is the motion E-flat to D.

M.22A – similar to a figure used by Lester Young.

M.23A – usually is the dominant pitch at the end of a chorus.

M.23B – easily produced by alternate fingerings of the same note; a favorite Lester Young motive.

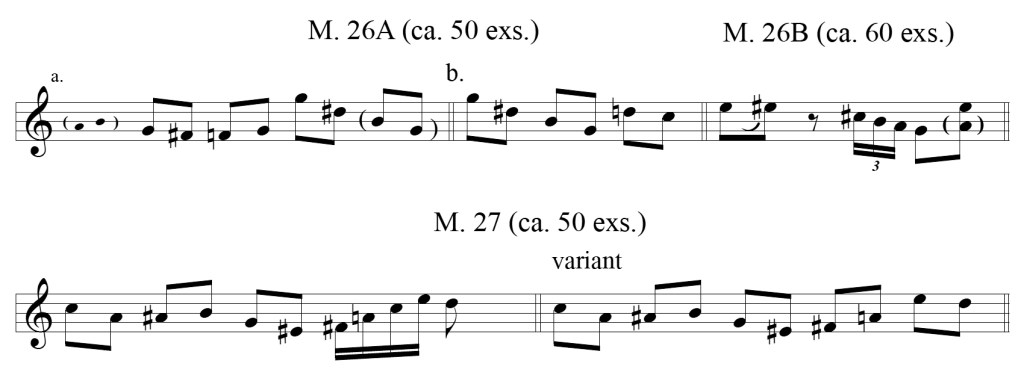

M. 26A – found only on A7#5 and G7#5.

M 29AB – Parker’s principal use of the blue third; usually occurs in G.

M.31a – the last note is an upper neighbor, not a chord tone.

M.33 – always occurs on G dominant seventh, but easy in most keys.

M.36AB – found almost exclusively in “Night in Tunisia”.

M.39 – found only in G, the easiest key for this motive

M.41 – a decorated form of M.1C; found only in A; a hard figure in any key.

M.42A – found only on E and D minor-seventh chords.

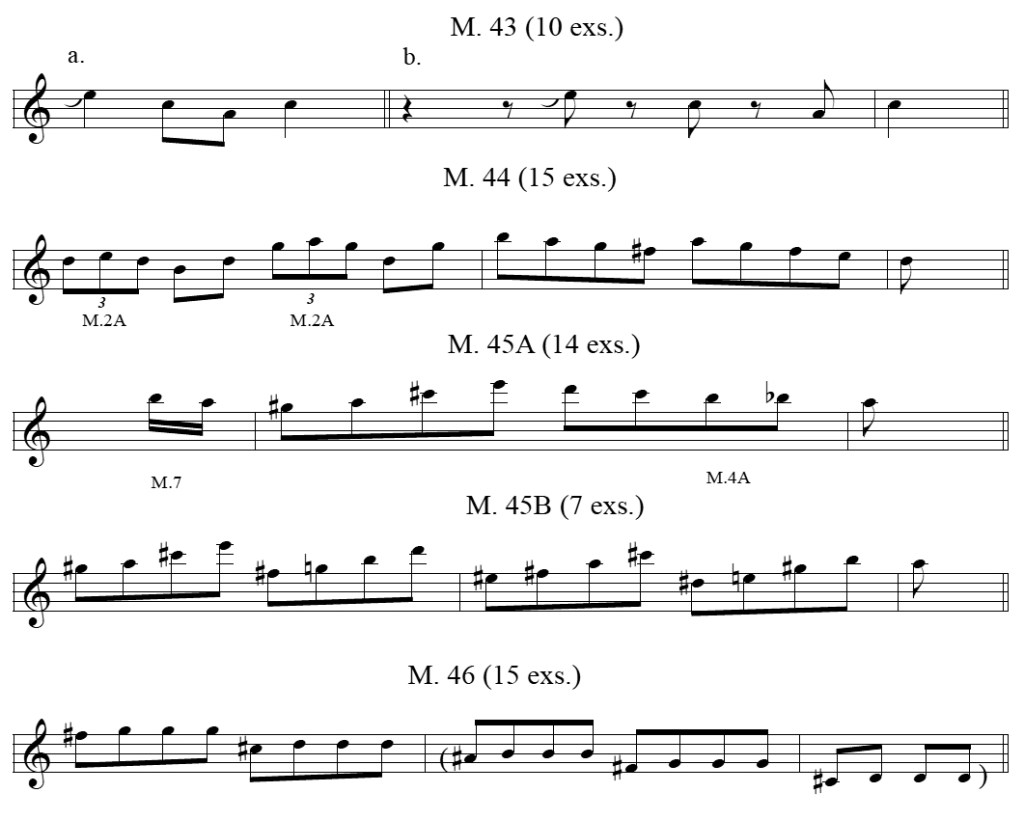

M.44 – the “High Society” motive (see pp. 29-30) almost always in G, the easiest key for this motive.

M.45AB – always in D.

M.47 – the preferred goal of glissando is B, although B-flat and C are also easy goals.

M.48 – usually begins a blues chorus in G.

M.49 – usually in G.

M.51 – always in A.

M.53 – the “Habanera” motive (see pp. 29-30)

M.55 – the “Country Gardens” motive (see pp. 29*30) used primarily as a coda.

M.57 – found only in “Night in Tunisia”.

M.58 – always in G.

M.59 – a difficult motive.

M.60 – found only in b. section of “I Got Rhythm” in G, probably because motions A# to B and C# to D are easy.

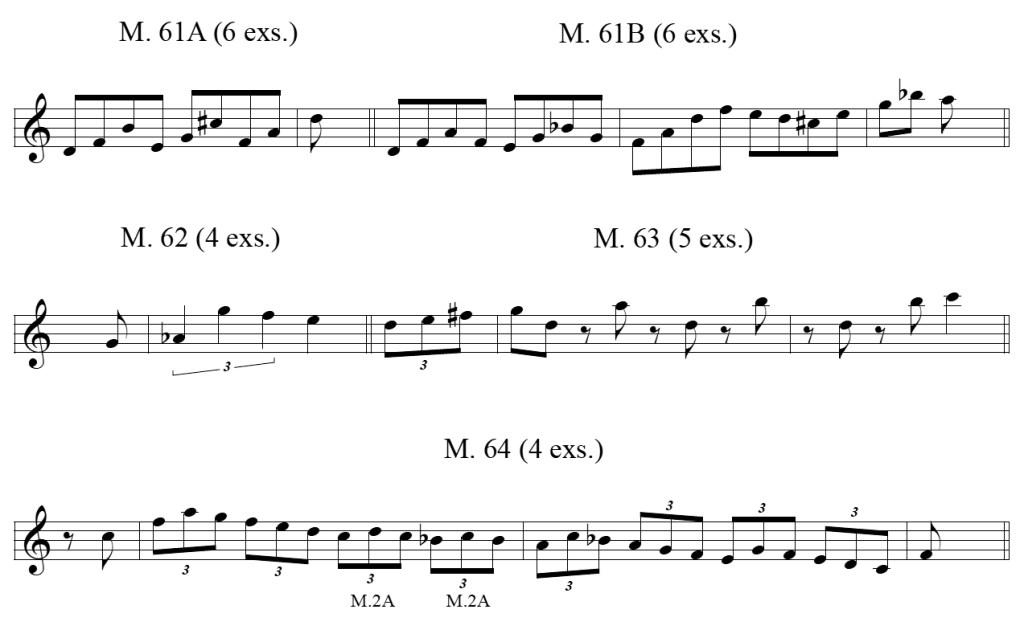

M.61A – always based on an D minor chord; a difficult figure.

M.61B – always based on an D minor chord.

M.63 – always in G.

M.64 – always in F.