John Purcell / youdoernie

You didn’t find many musicians who could show you on the piano what they were doing. But Charlie Parker could, even then. He was only a kid. We were both only kids. – Dizzy Gillespie

I’m using this page to present my hypothesis that Bird extrapolated much of his musical vocabulary from the first two songs he learned on saxophone, Honeysuckle Rose and Up A Lazy River (see Parkeology 005 & 006).

The archetypes derived from these tunes will be labeled with abbreviations and used to analyze Bird’s solos. I hope to make my case as efficiently as possible, so that anyone who can read music will get the point in a matter of minutes.

We will never know what Bird was thinking. All we have are the notes he played. And yet any meaningful attempt to analyze those notes is an attempt to understand the thought processes behind them. Since no inferred thought process can be proven right or wrong, the standard of judgment becomes plausibility: could Bird have been thinking this way?

By this measure, my hypothesis is all over the place, but I would rather speculate freely than confine myself to the most self-evident examples. This is really a thought experiment: imagine Bird had studied nothing else. How much vocabulary could he have derived from these two songs alone? Some suspension of disbelief may be required, but no matter how far I roam, my only assumption is that young Bird was capable of reordering the notes in any given bar, and/or transposing them by an octave.

Most examples are intentionally confined to a single Savoy recording date on 9/24/48 (Perhaps, Marmaduke, Steeplechase, Merry-Go-Round). If not, Cherokee (Ko Ko, Warming Up A Riff) provides the basis. Early solos with Jay McShann also appear (Honeysuckle Rose, I Found A New Baby), and Billie’s Bounce makes a cameo. All examples are notated in the key of C. All audio clips have been slowed down for greater clarity.

* * * * * * * *

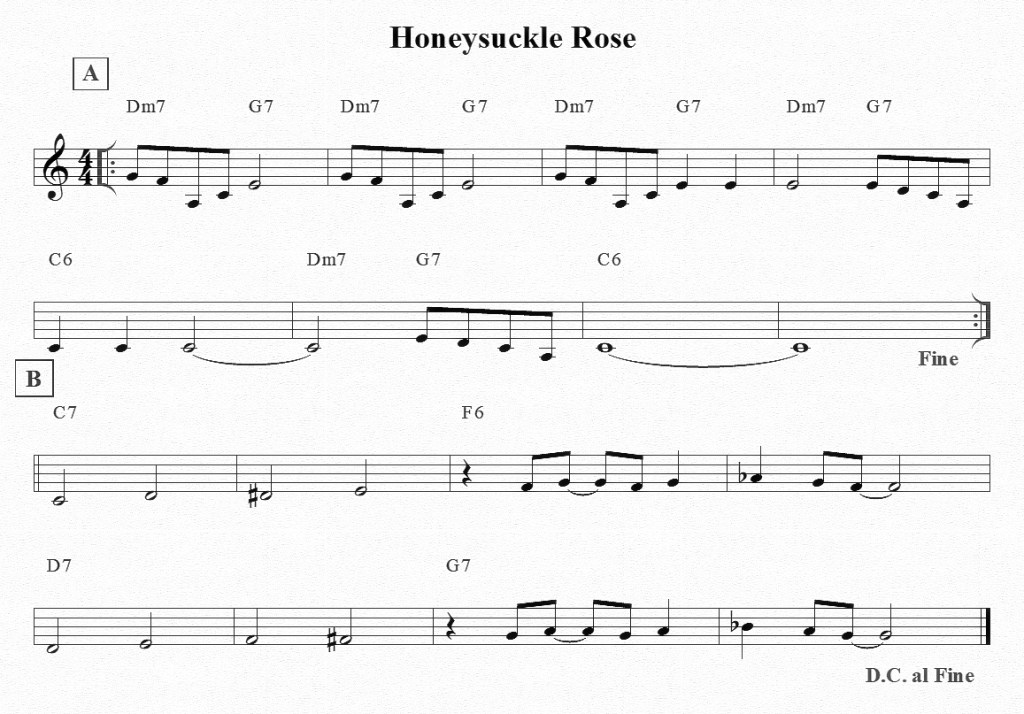

I’d learned the scale and I learned how to play two tunes in a certain key, in the key of D for your saxophone, F concert. I learned to play the first eight bars of “Lazy River” and I knew the complete tune to “Honeysuckle Rose.” – Charlie Parker

Around age 14, Bird decided to become a saxophonist. He taught himself the major scale and two tunes, Lazy River and Honeysuckle Rose.

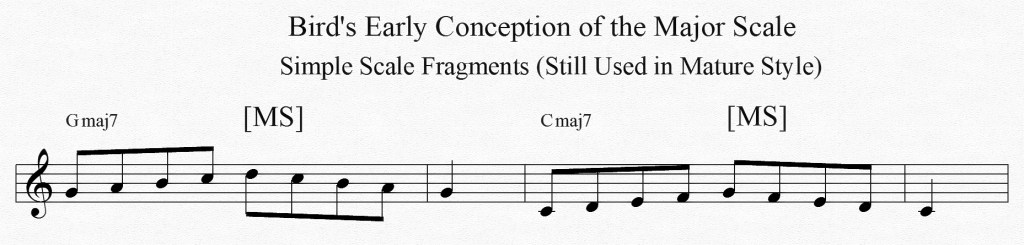

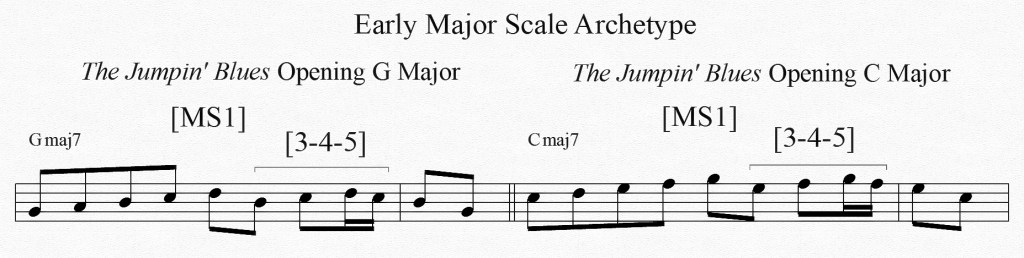

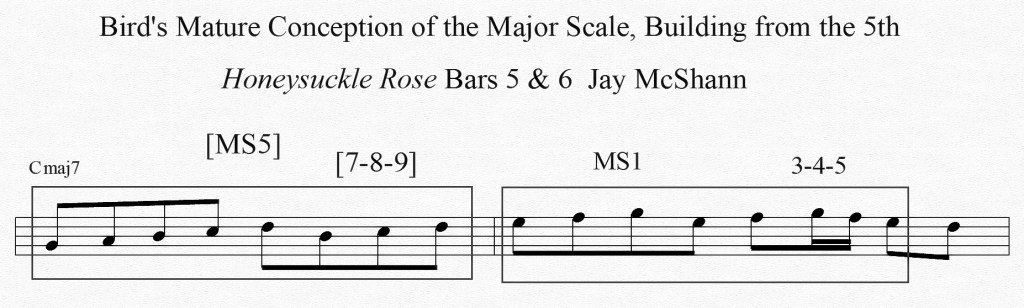

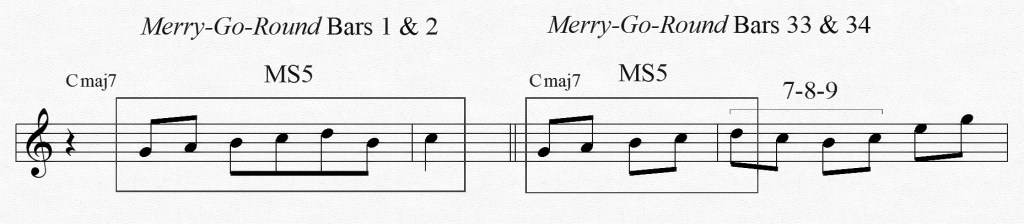

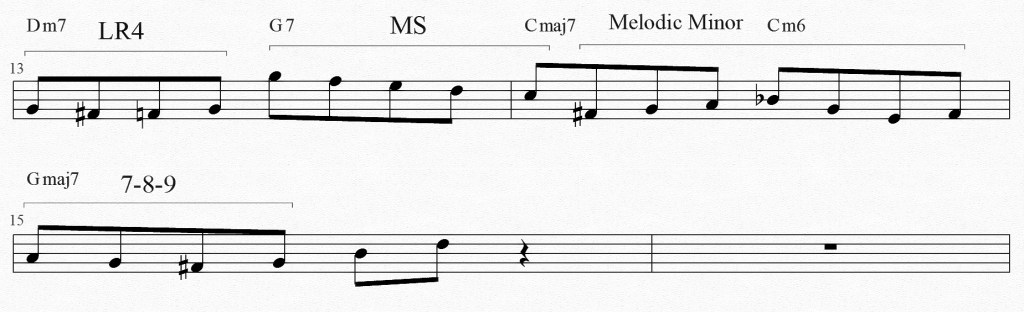

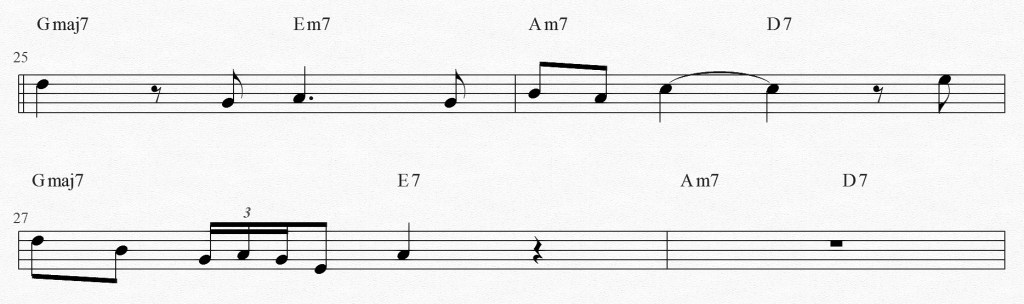

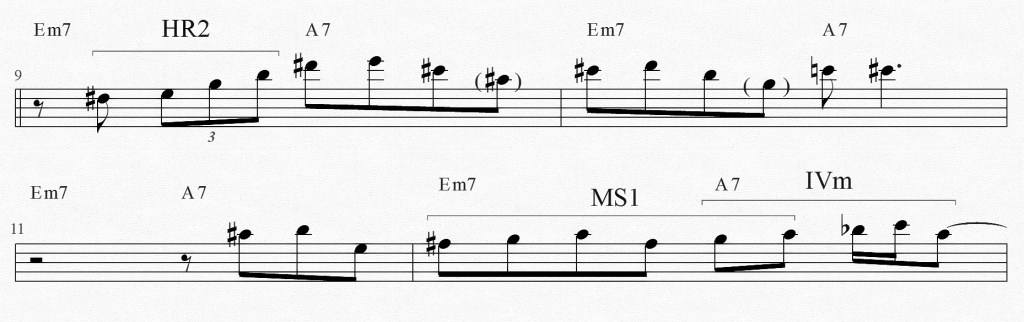

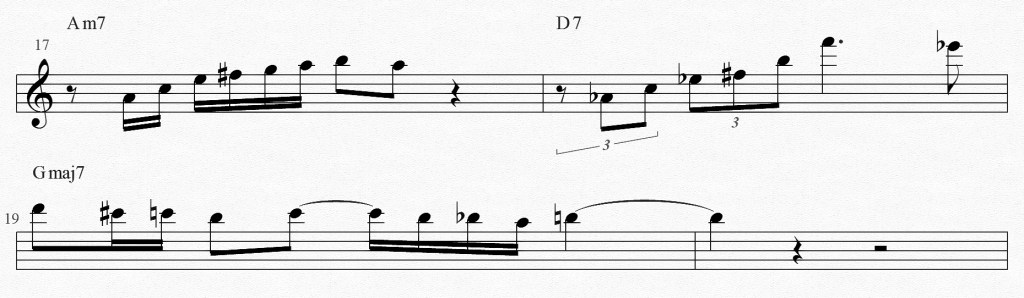

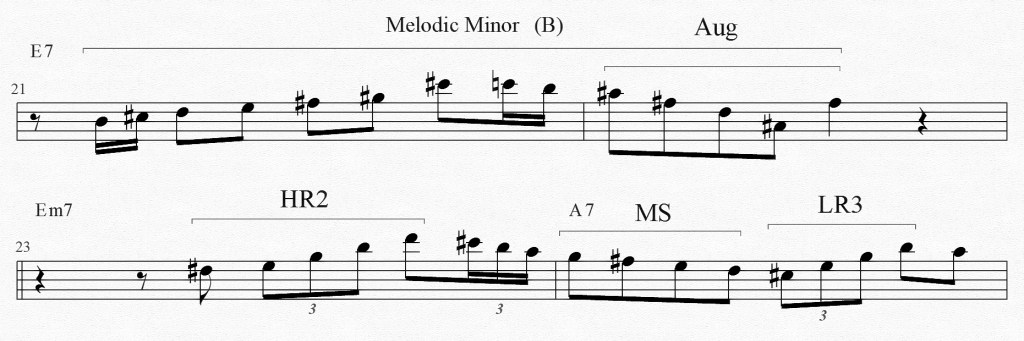

Even in his mature style, Bird uses simple major scale fragments, 1-2-3-4-5 or 5-4-3-2-1, to connect ideas together [MS]. His early major scale archetype was a run up to the 5th and back down to the root, with an ornament in the middle, centered on the 3rd, 4th, and 5th [MS1]. Sometime later, he realized he could build this run from the 5th, so that the ornament centered on the 7th, 8th, and 9th [MS5].

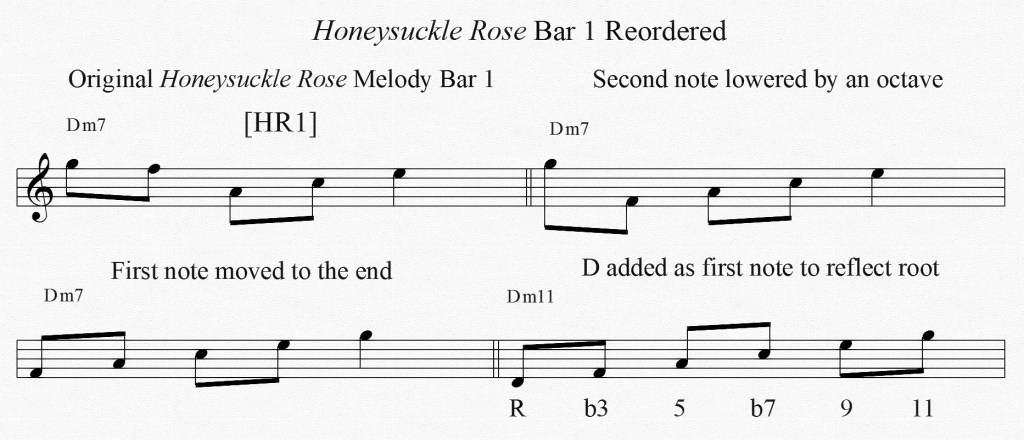

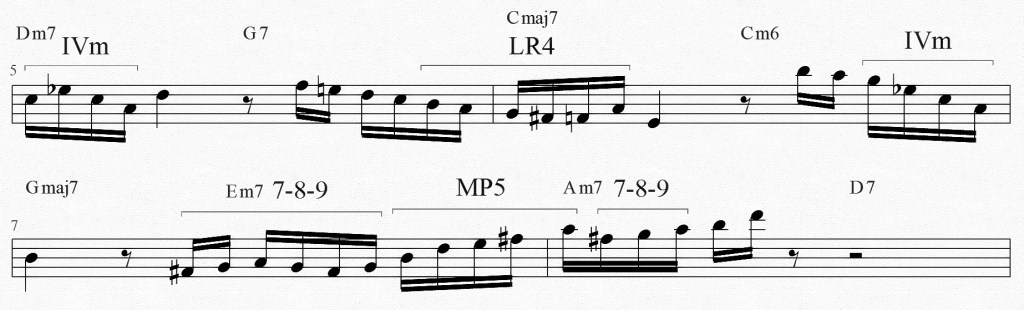

Bird discovered that the reordered notes in bar 1 of Honeysuckle Rose [HR1] spelled out a Dm11 chord. This stairway to the upper structures of the II chord had far reaching implications.

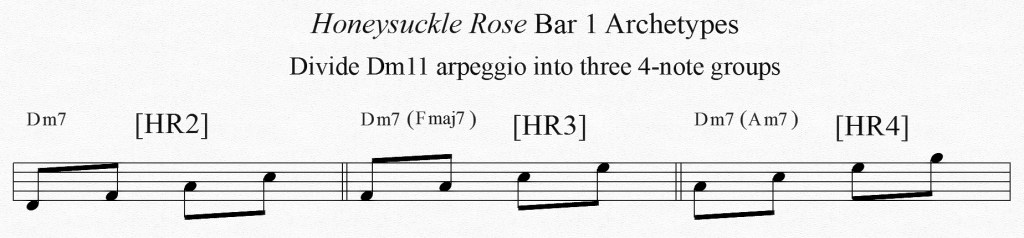

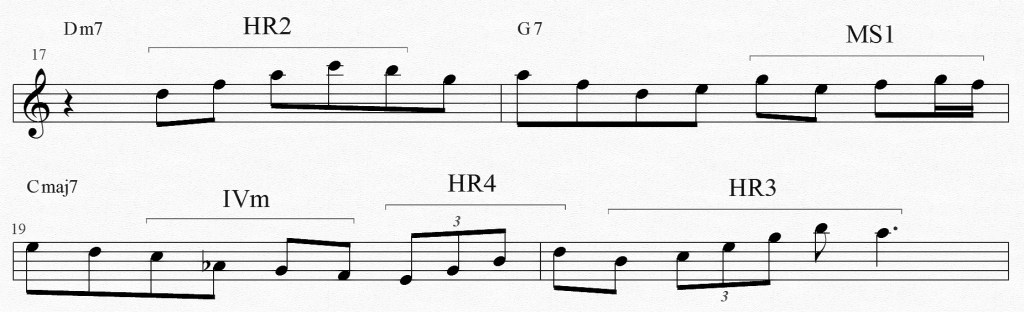

Bird divided these six notes into three 7th chords [HR2] [HR3] [HR4]. The archetypes start with an approach note and end with a downward whole step or half step. Triplets are usually part of the rhythmic structure. Note that HR3 sounds as Fmaj7 and HR4 sounds as Fmaj9

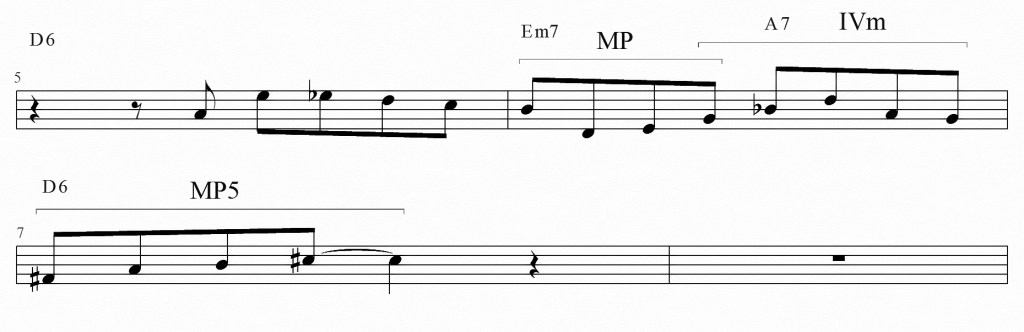

The last two phrases in the Honeysuckle Rose A section introduced Bird to the major pentatonic scale. He expanded on it by adding a b3rd approach note, a concept suggested by the bridge melody. He also added the 5th on the bottom. This archetype was essential to his blues playing [MP].

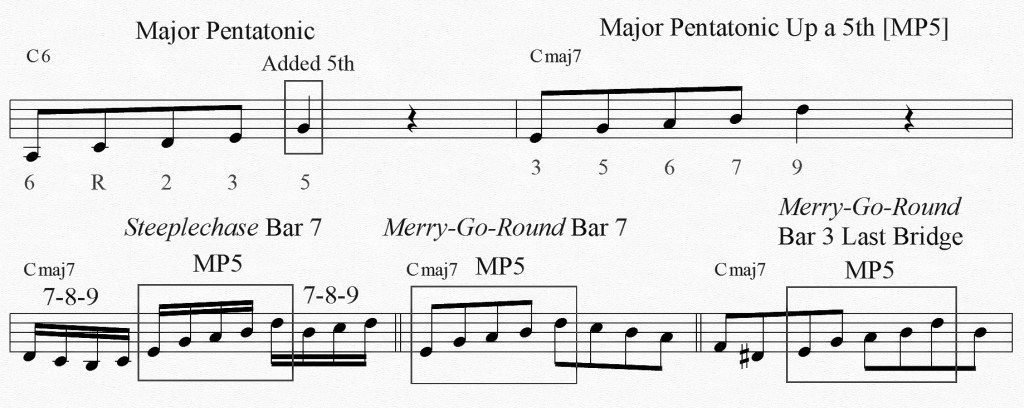

Bird also made use of the major pentatonic scale in a less obvious way, building it from the 5th. This archetype is somewhat different, with no b3, and with the 5th on the top [MP5]. He used it quite often on major I chords.

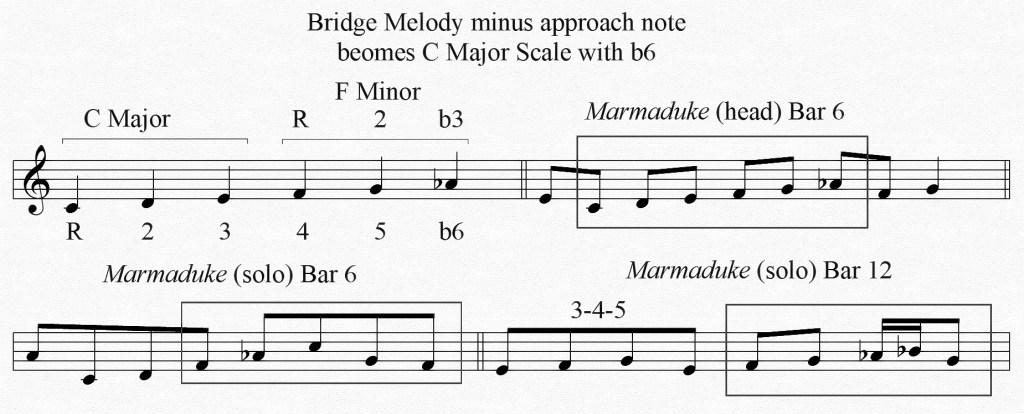

The bridge melody without the approach note can be viewed as a major scale with a b6. This acted as Bird’s guide to IV minor, an important element in his vocabulary.

Bird’s IV minor archetypes [IVm] are short, descending four-note blocks that he often superimposes over V chords and major I chords.

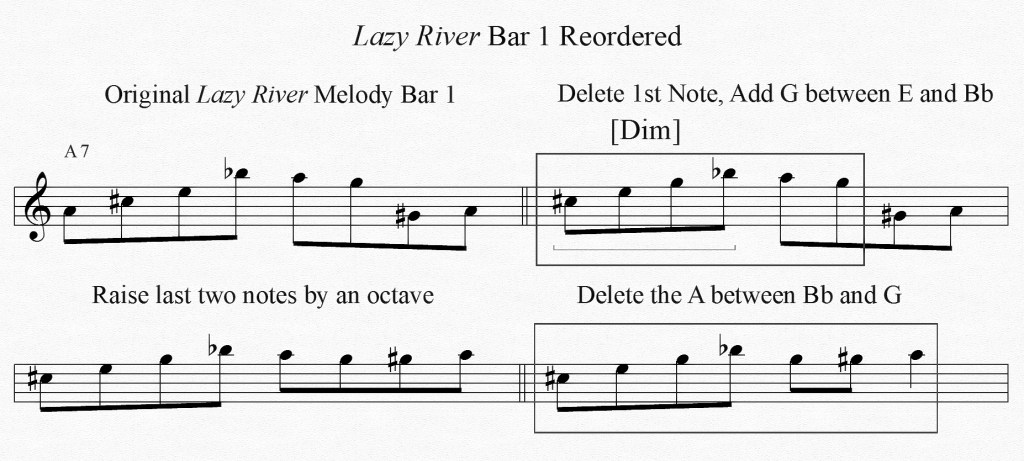

By reordering the notes in Lazy River bar 1, Bird discovered the diminished 7th chord, which creates the dominant 7(b9) sound [Dim]. Further reordering resulted in one of his most common archetypes [LR1].

All archetypes that involve the dominant 7(b9) sound are labeled LR1.

Bird has an analogous archetype for major chords [LR2].

Bar 2 of Lazy River introduced the concept of augmented chords [Aug], demonstrating that they’re an alternative to diminished 7th over V chords.

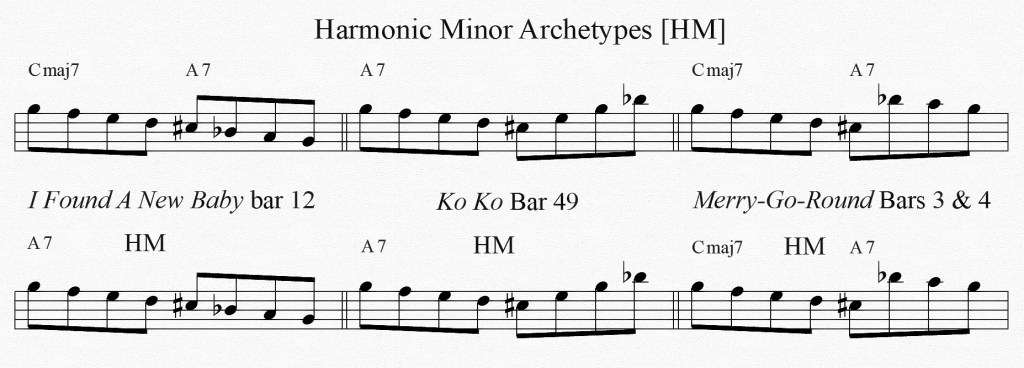

The only minor scale that produces diminished 7th chords is harmonic minor [HM]. Bird deduced this from bar 1, and he uses harmonic minor almost exclusively. (Melodic minor takes second place.) The three archetypes represent the most common forms.

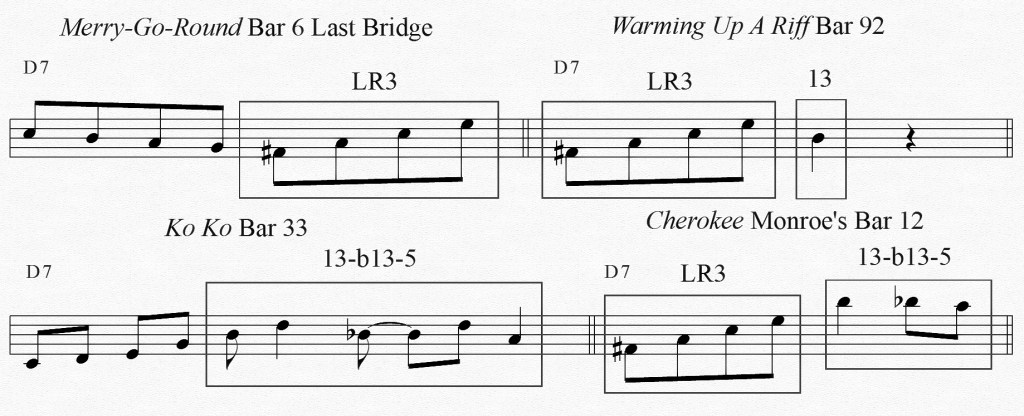

Bird derived another common archetype from bar 3 of Lazy River [LR3]. Whenever he arpeggiates a dominant 7th chord, it’s almost certain he’ll run it upward from the 3rd to the 9th. Bar 4 is a primer on 13ths, spelling out 13-b13-5 on top of the V chord [13-b13-5]. A consistent archetype is hard to define, but Bird uses 13-b13-5 in many contexts.

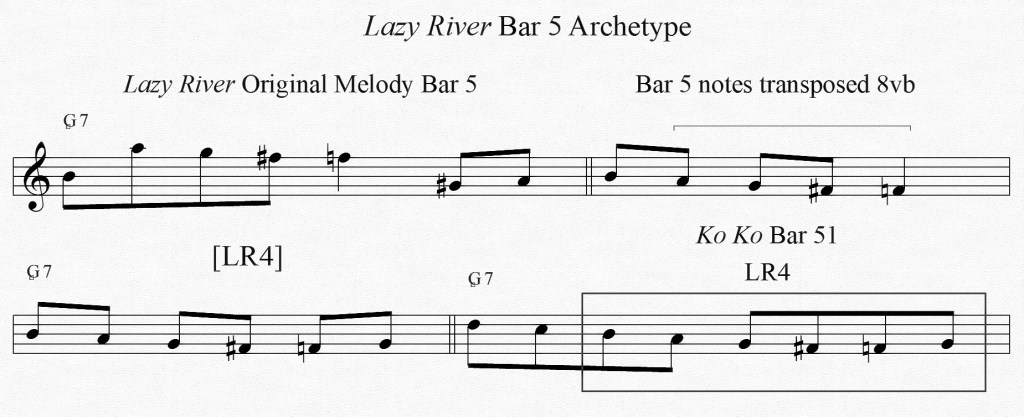

The notes in bar 5 [LR4] became one of Bird’s most common chromatic archetypes, used over dominant 7th chords.

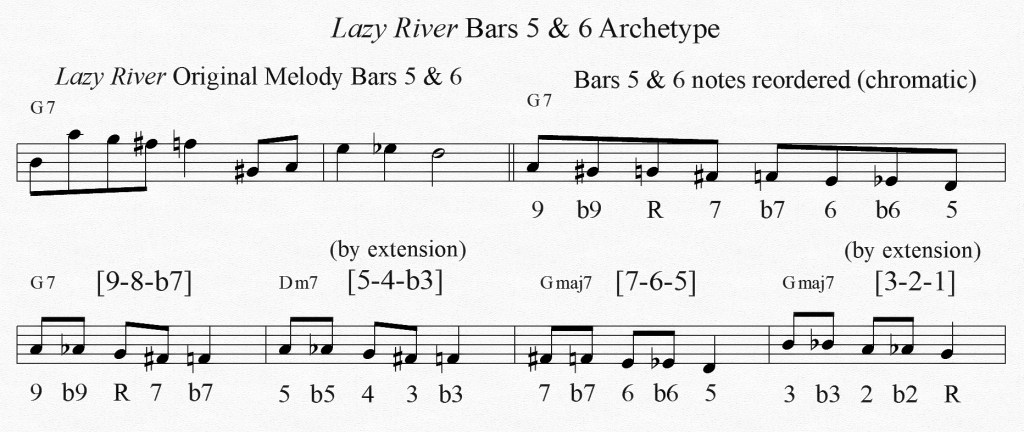

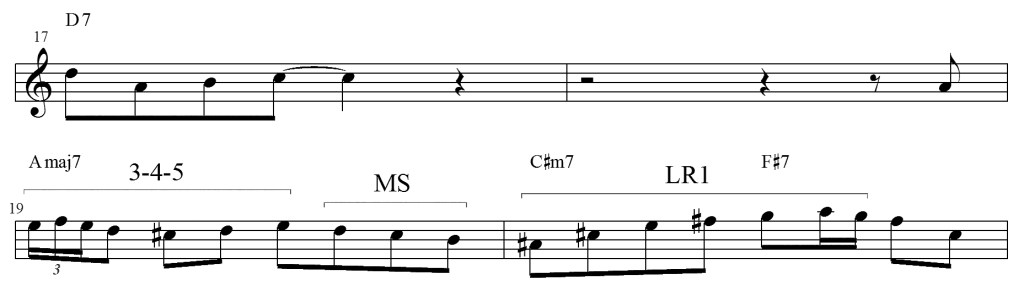

The combined notes in bars 5 & 6 can be reordered into a chromatic scale that descends from the 9th to the 5th. Bird divides these eight chromatic notes into smaller groups, five being the magic number. [9-8-b7] and [7-6-5] come from this specific scale, but he extended this concept to include [5-4-b3] and [3-2-1].

I will conclude this inventory of archetypes with a question: Did Bird ever finish learning the Lazy River melody? For the sake of argument, let’s say yes, because he uses the bar 14 archetype constantly [LR5]. These five notes are identical to the “bebop scale.” Could that scale’s humble beginnings lie in Lazy River? Say what you will, there it is.

* * * * * * * *

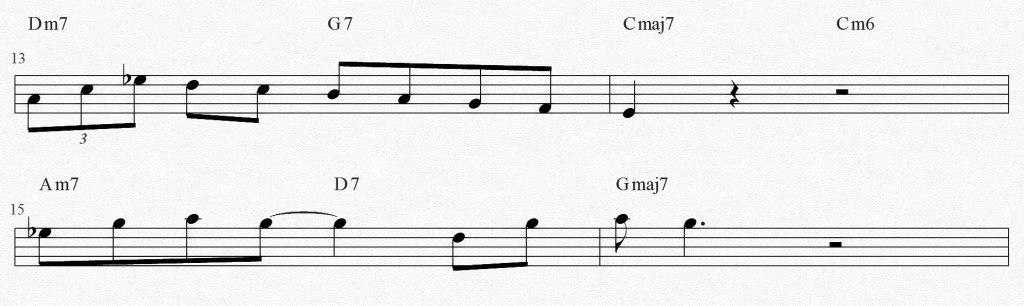

Onward to Bird’s solos, all from the 9/24/48 Savoy date (Perhaps, Marmaduke, Steeplechase, Merry-Go-Round).

Although recorded last that day, Merry-Go-Round will go first here. Even Bird has to rely on his reflexes at such fast tempos, making it easier to identify basic archetypes.

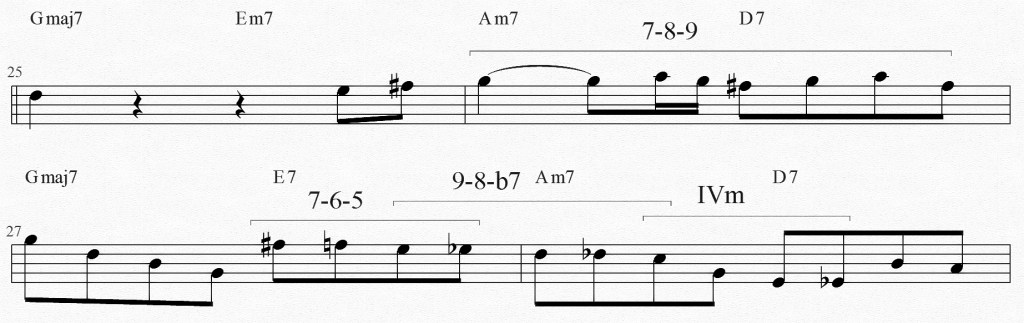

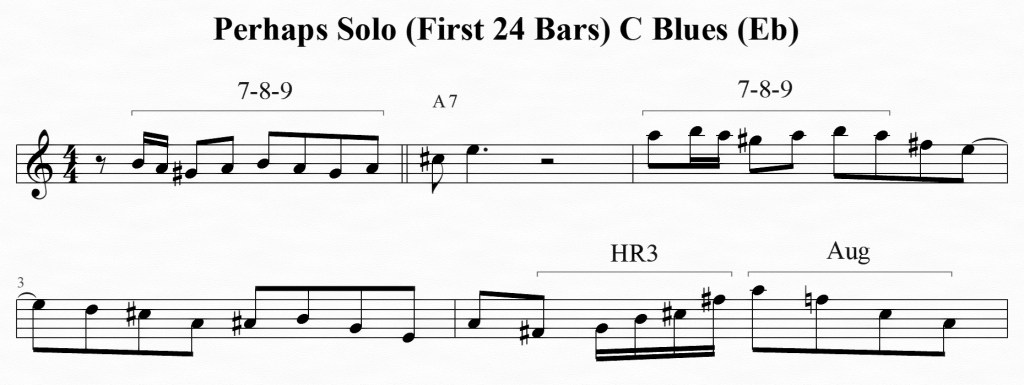

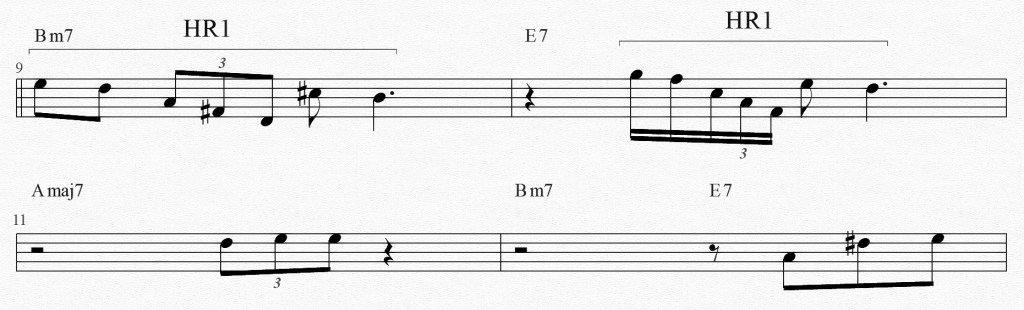

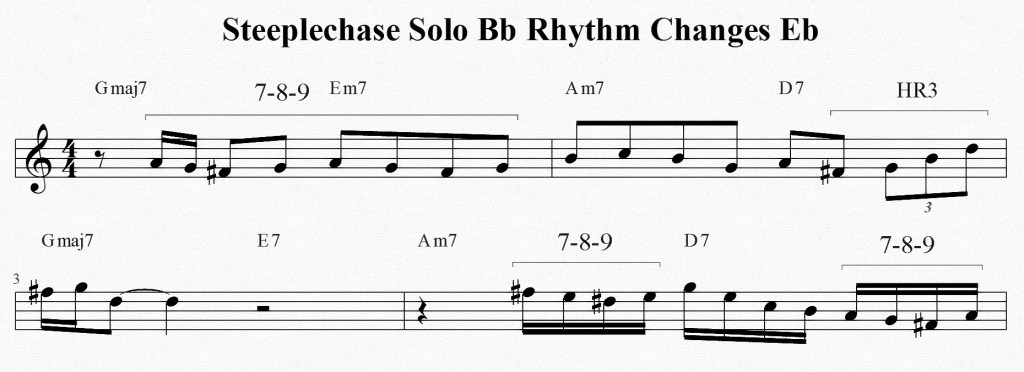

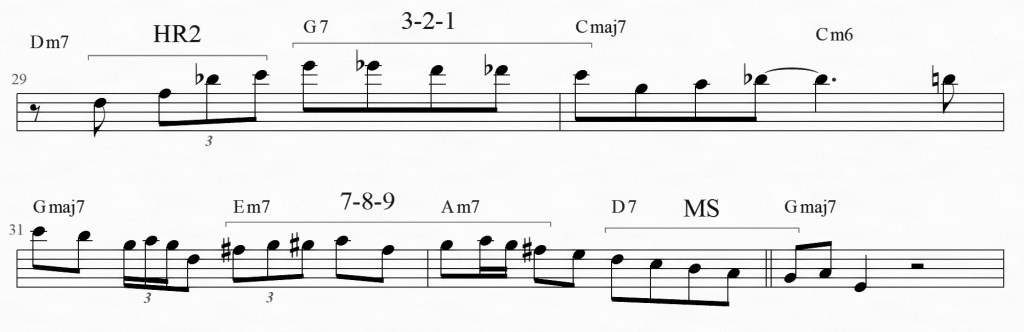

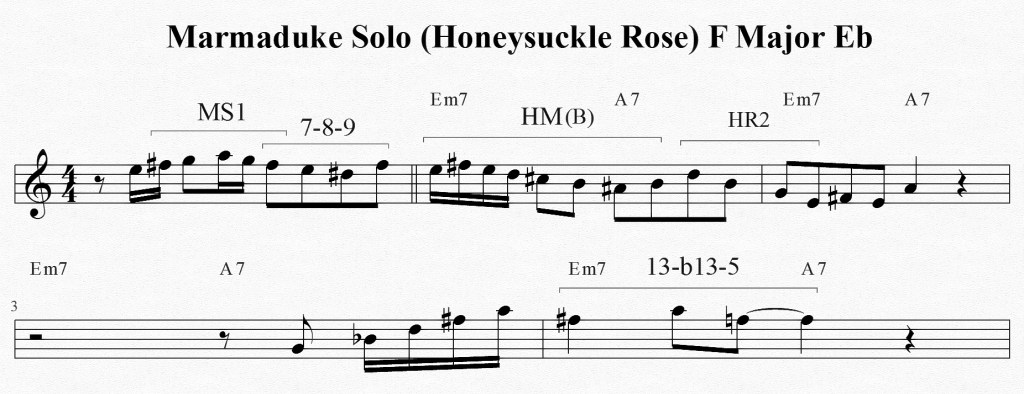

Perhaps required seven takes, which documented a highly unusual phenomenon: Bird starts all seven solos with the same opening phrase, based on the 7-8-9 archetype. He has no qualms about using the leading tone (G#) over the A7. Bird repeats this opening phrase in Steeplechase.

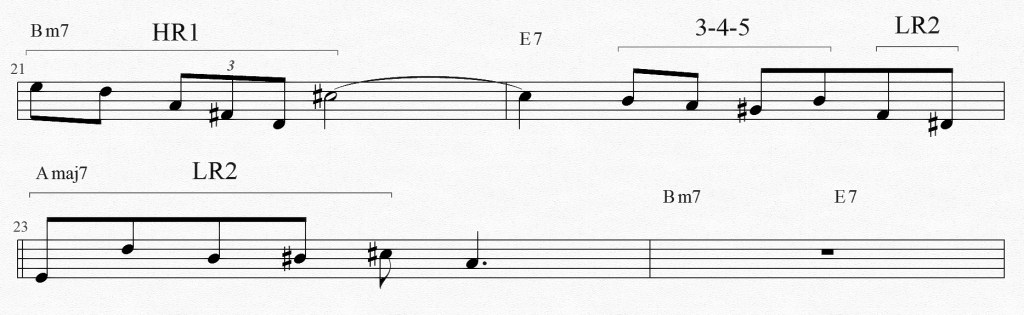

Bird pulled off Steeplechase in one take, perhaps due to its relative simplicity and relaxed tempo. He launches into double time early on, which brings out an array of archetypes, but the overall mood is serene. He returns to double time in bar 21, tearing off his most reflexive of all runs, half Honeysuckle Rose, half Lazy River.

Honeysuckle Rose remained a touchstone throughout Bird’s life, not least because it’s the basis for Scrapple From The Apple. In that instance, he swapped bridges with I Got Rhythm, but the Honeysuckle Rose bridge appears in other compositions, including Merry-Go-Round. Marmaduke, however, is the only reimagining of the original Honeysuckle Rose form.

* * * * * * * *

I was crazy about Lester. He played so clean and beautiful. But I wasn’t influenced by Lester. Our ideas ran differently. – Charlie Parker

It’s hard to know what Bird meant by this, since Lester’s influence seems beyond dispute. The above hypothesis, while rife with speculation, at least points toward an answer. Bird was a genius, and he began forming his vocabulary at fourteen or fifteen, years before Lester’s first recordings came out. It’s hard to believe he wouldn’t have developed many of his own ideas before he had the chance to study Lester’s solos. Could this be what he meant?

Perhaps.